The Ulster Kingdoms

The Country of the Cruthin.

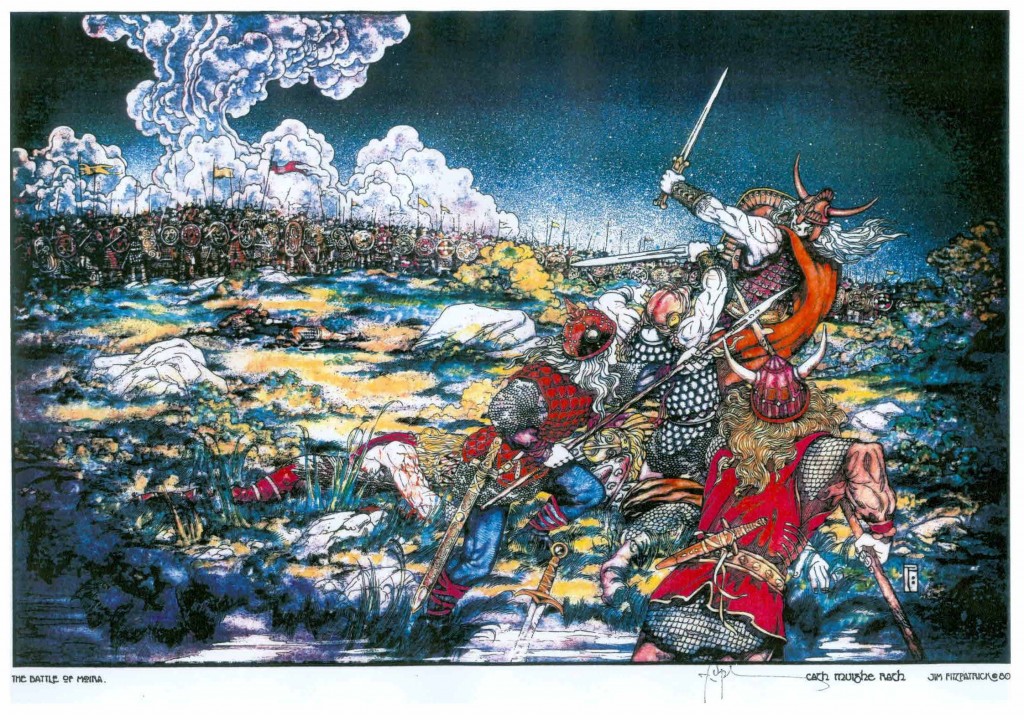

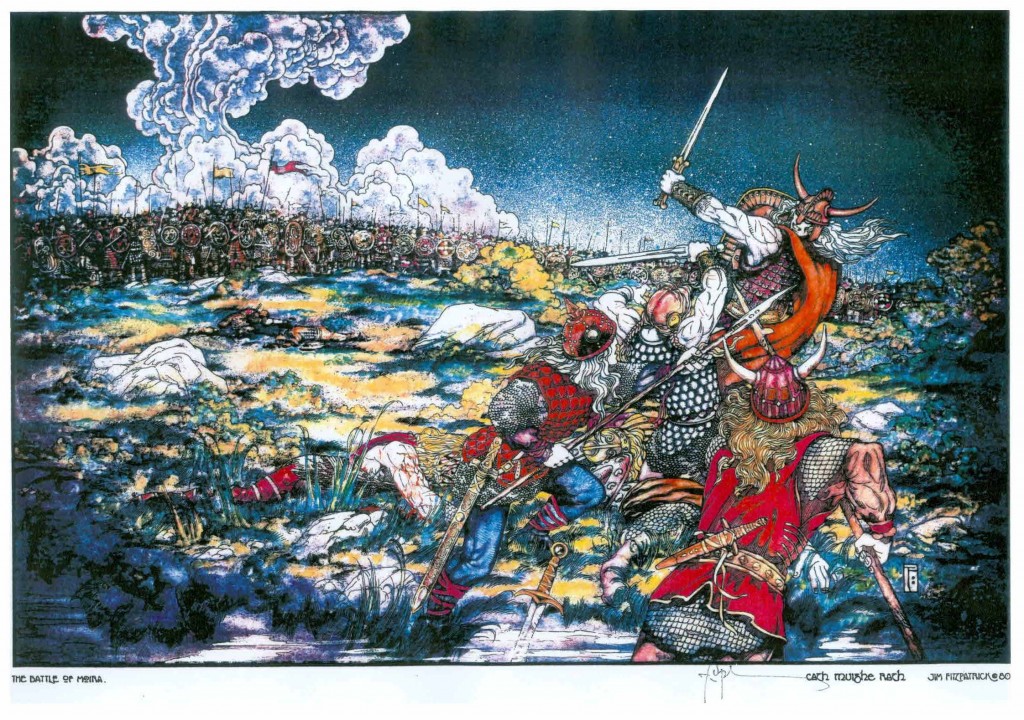

The Parish of Glenavy, which is a Brittonic or Old British name, later Gaelicised, is rich in legendary and historical associations. The ancient name of the territory lying along Lough Neagh and stretching from Larne to Magheralin was The Country of the Cruthin (Cnoc na Cruitne), or so-called “Irish Picts”. The earliest inhabitants of this territory of whom we have any record are described in the Book of Lecan as the race of Conall Cearnach. They claimed descent, therefore, from one of the noblest of the Red Branch Knights, Conall the Victorious (Conall Cearnach). The old Irish genealogies trace their descent back to another of the Red Branch Knights, Keltar, who lived near Downpatrick, at a place still called Rath Keltair ; they tell us that Neim, the daughter of Keltar, was the wife of Ailinn, son of Conall Cearnach. These Red Branch Knights, according to the ancient legends, were the great warriors of the North about the time of Christ. Their King, who ruled the Province of Ulster, was Conor Mac Nessa, and his residence was the famous Palace of Emania. Navan Fort, about two miles outside the city of Armagh, still marks the place where the palace stood. In all the wars that Conor Mac Nessa waged against Queen Maeve of Connacht and the other provinces, Conall Cearnach, Leary, Keltar, and the mighty hero Cuchullain were ever foremost in the fray. And when the enemies of the Ulster King were beaten off and peace restored, the victorious chieftains would return home each to his own stronghold, and there they led an enterprising life. Now they would feast and revel with their retainers, and the banquet-hall would ring with merry song and boisterous laughter. Again they would ride forth with wavy crest and glittering spear to hunt the wild boar over mountain, wood, and glen. Such was the life of chieftain and warrior in those far-off days in Heroic Ireland, when Patrick had not yet set foot on Irish soil, nor had the light of Christianity come to dispel the gloomy clouds of Paganism : for Paganism, with all its careless., joy and revel, left the minds of thoughtful men a prey to-dread anxiety as to the unseen world to come.

The Territory of Dalmunia

The Civil Parish of Glenavy lay within the boundaries of the ancient Dalmunia. (Dal mBuinne= the race of Buinne, son of Fergus Mac Roy). This gives it another link with the legendary past. The territory of Dalmunia, or, as it is sometimes called, Dalboyn, included also Kilultagh, Kilwarlin, Hillsborough, and Lisburn, and was peopled by the race of Fergus Mac Roy, the ancient British Cruthin Fergus was King of Ulster about the beginning of the first century A.D. He wished to marry the beautiful widow Ness. She would not give her consent unless on the understanding that her son Conor, then a mere boy, should be allowed to be king for a year. To this Fergus, with the consent of the nobles, agreed. When the year was up, the queen-mother had guided her son so wisely in the use of his power that the nobles now refused to supersede Conor. This is what the mother had anticipated. And so Conor Mac Nessa remained King of Ulster Fergus Mac Roy acquiesced in the situation, and became chief-counsellor of Conor and tutor of the infant-hero Cuchullain. Some years later, when war broke out between Conor and Maeve of Connacht, we find Fergus as chief-counsellor of Queen Maeve. He had abandoned the service of Conor, and not without good reason. Naoise, one of the nobles, had eloped with Deirdre, the most beautiful of the women of Erin, who was destined to be the wife of King Conor himself. “Therefore, accompanied by Deirdre and his own two brothers, Ainle and Ardan, the sons of Ushna, he fled from the anger of Conor into Scotland. They remained in exile many years, and Conor and Fergus pledged their word of honour that, if they returned home again, they would be unharmed. Deirdre had a foreboding of evil, but the sons of Ushna calmed her fears, and they all returned home. In spite of the royal guarantee, however, they were foully put to death. Fergus Mac Roy could not brook to be a party to such treachery, and it was for this reason he abandoned the Ulster King and took service with Maeve of Connacht.

These are but specimens of the numerous legends that group themselves around the ancient inhabitants of Antrim, Down, and Armagh. No one to-day would venture to put them down as serious history. But the folk-lore of a people cannot be utterly discarded. The stories of the ancient heroes reveal the ideals of a remote antiquity, and the events described must have been founded on real deeds of heroism that were exaggerated and glorified as they were told and retold round the hearth to each succeeding generation.

THE CREW HILL.

Its Historical Importance.

The subsequent history of Glenavy is closely connected with that of the Kingdom of Ulaidh or Ulidia. The Kings of Ulaidh were proclaimed on the Crew Hill, on the eastern side of the parish, visited regularly by the Dalaradian organisation. The coronation-stone is still to be seen on the summit of the hill, but the “spreading tree,” under which the ceremony took place, and from which the place itself is named, was cut down in 1099 by the Clan Owen, the hereditary enemies of the Ulidians. There is a large rath, which may have been the royal residence, on the south side, as you approach the top of the hill. On the summit there have been discovered some stone-lined graves belonging to the Pagan period. Nothing more remains to mark the scene where many a time the clansmen of Ulaidh gathered round their king from far and wide, to be drilled and marshalled for many a fierce encounter.

Then and Now.

The hill itself rises to a height of 629 feet, and commands a view of the entire parish. From the top of the Crew the scene that lies before the visitor on a summer’s day is one not easily to be forgotten. On the west, Lough Neagh stretches away in the distance to where Slieve Gullion and the grey-blue hills of Derry and Tyrone are dimly visible. Ram’s Island, with its clump of trees reflected in the water, seems to float upon the placid surface of the lake ; while here and there a flying sail betrays the Lough Neagh fishermen. In the centre of a picturesque landscape, that lies between us and the shore of the lough, we notice Chapel Hill – an eminence crowned by the Parish Church and Parochial House. The sheltered homesteads of the farmers seem to be within easy reach of one another ; while at some little distance towards the north we see the village of Glenavy half-hidden amongst the trees. We turn towards the south, and the rich plains of Down are stretching out before us. Here and there are towns and villages nestling amongst the woods and by the streams. In the distance far south our view is bounded by the Mourne Mountains, that keep eternal sentinel along the Irish Sea. On the north, the fertile tract of country lying around Crumlin, Antrim, and Templepatrick meets our view, and on a clear day the hills of Mid-Antrim are outlined upon the horizon. The eastern side of the hill presents a contrast to the other three. Here one sees the bleak mountainous district of the Rock ;and Stoneyford, threaded by the lonely roads that lead from Glenavy to the busy city of Belfast. Truly, it was a site well-chosen – this ancient stronghold of the Kings of Ulaidh. The traveller to-day, as he gazes on the quiet country-side, with its fields of golden corn and verdant pasture-lands forgets that these fair plains were many a time and oft the scene of furious battles.

THE KINGDOM OF ULAIDH.

The Fall of Emania.

The Crew Hill came into prominence in Irish history after the destruction of Emania, in 335 A.D. Up to that time Emania was the centre of royal power for the whole Province of Ulster. Its King, according to the Book of Rights, had the privilege of sitting by the side of the King of Erin, and held first place in his confidence. The Palace of Emania yielded in fame and magnificence only to the Palace of the High-King at Tara. At the dawn of history it had a storied past. It had been founded by Queen Macha of the Golden Hair three centuries before the Christian era. It reached its highest glory in the time of Conor Mac Nessa and his Red Branch Knights.

For six centuries, therefore, the King of Emania was Sovereign of all Ulster and sometimes also High-King of Ireland. But in the century before St. Patrick evil days came upon it. The three Collas are reputed to have made war upon the Ulster King, plundered his territory, and burned the palace, around which centred the romantic tales of the Red Branch Knights. The Ulidians were driven eastwards over Glenree, or the Newry River. They took their name with them into their circumscribed territory. From this time onward the term Ulidia, or Ulaidh, is applied to the tract of country lying to the east of Lough Neagh and the Newry River. Sometimes the Plain of Muirtheimhne, or North Louth, was included ; but indeed the boundaries of territories in those days were continually fluctuating, according to the power of each new sovereign to annex the territory of his neighbours.

The King of Ulaidh, then, who was crowned and proclaimed on the Crew Hill, had subject to him the Kings of Dalaradia, of Dalriada, of Dalmunia, of Dufferin, of the Ards of Dal Fiatach, of Lecale, of Iveagh, and of several minor provinces.

Circumscribed Ulaidh.

It would take too long to follow the fortunes of the Kingdom of Ulaidh through all its chequered history. The law of succession was a fruitful source of strife at home. According to the Irish custom, the heir to the throne was not the eldest son, but the member of the royal family, or royal blood, who was adjudged most worthy. This gave a constant pretext to rival claimants. And the enemy abroad was ever on the watch. The Clan Owen were ready at all times to take advantage of Uladh’s difficulty or temporary weakness. Hence, as years went on, the King of Ulaidh, who had at first aspired to regain his lost sovereignty over Ulster, found himself at length unable to hold his power over his tributary kings and princes.

Battle of the Crew Hill.

One or two events cannot be passed over. The first is the Battle of the Crew Hill, in 1003 A.D., in which the Ulidians were defeated by their old enemies, the Clan Owen. From the account of the Four Masters, we see what enormous forces were engaged : ” In this battle were slain Eochy, son of Ardghair, King of Ulaidh, and Duftinne, his brother; the two sons of Eochy, Cuduiligh and Donal ; Garvey, lord of Iveagh ; Gillapadruig, son of Tumelty ; Kumiskey, son of Flahrey Dowling, son of Aedh ; Calhal, son of Etroch ; Conene, son of Murtagh ; and the most part of the Ulidians in like manner ; and the battle extended as far as Duneight and Drumbo. Donogh O’Linchey, lord of Dal-Araidhe and royal heir of Ulaidh, was slain on the following day by the Clan Owen. Aedh, son of Donal O’Neill, lord of Aileach and heir-apparent to the sovereignty of Ireland, fell in the heat of the conflict, in the fifteenth year of his reign and the twentieth year of his age.”

Brian Boru at the Crew Hill.

Two years later another important event occurred–the visit of Brian Boru to the Crew Hill. It was nine years before the Battle of Clontarf. Malachy, of the Southern Uí Néill, had been deposed from the High-Kingship, and Brian acknowledged in his place by almost the whole of Ireland. The Clan Owen and the Clan Conall still sympathised with Malachy and his adherents. The King of the Clan Owen had fallen in the Battle of Crew Hill, and Brian thought the time opportune to march northward and secure the submission of the Ulster chieftains. The expedition arrived at the Crew Hill in 1005 A.D., and the Ulidians tendered their allegiance. The Wars of the Gael with the Gall describes the provisions supplied to the army of Brian while he was encamped there : “They supplied him there with twelve hundred beeves, twelve hundred hogs, and twelve hundred wethers ; and Brian bestowed twelve hundred horses upon them, besides gold and silver and clothing. For no purveyor of any of their towns departed from Brian without receiving a horse or some other gift.” But although Brian was well received by the Ulidians, he had to depart from Ulster again without receiving the submission of the Clan Owen or Clan Conall.