Introduction: Minister, Mr Deputy Mayor, President of UCC, ladies and gentlemen

Introduction: Minister, Mr Deputy Mayor, President of UCC, ladies and gentlemen

I’m hugely grateful to have been invited here to Cork to join you at this important conference. The Centenary that is about to break upon us offers an opportunity to set the developing relationship between our two countries in a deeper context. And, I hope, improve it.

What a great legacy that would be. What a tribute to the fallen. Ours is a complex and nuanced relationship that is now, in the 21st Century, going well. Today’s better times are epitomised by PresidentMcAleese’s invitation to the Queen to visit Ireland in 2011 – during which some of you may recall a walkabout here in Cork to enable the Queen to meet members of the public.

It is a relationship that was further deepened by the visit of the Taoiseach and David Cameron to the Menin gate and to Messines last month. And it will be capped by President Higgins’ visit to Britain this year – the first Irish head of state to make a state visit to the UK.

The British Head of State has of course been here before – a hundred years before.

Great Britain’s decision to go to war in 1914

In Britain we have already had some spirited debate about how we – and, for better or worse, it was ‘we’ in 1914 – came to be engaged in the First World War and whether our involvement was just, ultimately, in the terms of St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas. One interpretation has us sleepwalking into a tragically wasteful and pointless conflict – a proposition advanced by Christopher Clark and popular in Germany.

Alternatively it can be seen as the inevitable result of naval rivalry between Britain and Germany as muscular Germany elbowed its way for a place in the sun. Whatever the war’s origins, it is a fact that Germany took full advantage to pursue a military campaign that had been designed some years previously. But was it necessary for Britain to enter the war?

Witness the amorous Liberal PrimeMinister Herbert Asquith’s comment to his lady friend Venetia Stanley as matters came to a head in the Balkans that July: ‘Happily, he said to Venetia, there seems to be no reason why we should be anything more than spectators.’ Just the sort of remark gentlemen to include in a letter to your girlfriend.

Many historians and commentators these days may well agree with Asquith’s mindset of July 1914. In short that, leaving aside our treaty obligations to Belgium, Britain could have stayed out of the war. Sure such an approach would have brought problems – German hegemony on the Continent – or, had France and Russia won, pressure on wider British interests. On the other hand, to many now – and especially at the time – it was a war of survival in which there was a direct existential threat to UK.

The different circumstances of World War 2

The advocates of Britain maintaining splendid isolation in 1914 would perhaps argue that the consequences for Britain’s interests could not have been worse than the horror unleashed by the Second World War, which most of us agree was causally linked to the first. And perhaps that’s the point.

Because of the Nazis, involvement in 1939 is not generally contested in the UK, nor is the status of 1939-1945 as a Just War. And although by that time Britain and Ireland had become separate states tens of thousands of Irishmen fought in the allied forces and served with great distinction. Hitler and the Nazis are popularly seen as the distillation of evil where Wilhelminic Germany is not. From that flows a sense of meaning to the sacrifices that were made between 1939 and 1945.

But what of the First World War? Well, if you regard the UK’s involvement as unnecessary then self-evidently the sacrifices were themselves unnecessary. However, if you take what I think is the majority view – and it is one that I hold – then the war was necessary and was just at the point at which Asquith’s Liberal government committed to it. Herein lies the problem and is central to our discussion today. A just war is one thing.

But a just war in which men are slaughtered on an industrial scale and in which there remain accusations of chaotic military management – ‘Lions led by Donkeys’ – is something else. Was the war futile or was the way in which it was conducted futile? At the confluence of these strands of thought congeals the classic vision of a meaningless bloodbath. An affront to all reason. And if futility becomes the leitmotif we are bound to see death in the First World War as qualitatively differently from death in the second. I believe that that is wrong.

Shared involvement

In Ireland, I am very conscious of the efforts being made by the President, government ministers and others to revisit the contribution made by Irish men and women in the First World War. At a symposium last week in Dublin, President Higgins said that: “It is crucial that we endeavour to do justice to the complexity of the historical context.” The President welcomed the fact that historical studies in Ireland had largely departed from a narrow, nationalist view of the Great War.

Much of our experience of that conflict in Britain and Ireland is shared. Certainly the war effort was supported by both Nationalists and Unionists with members of both communities joining the army in large numbers. The sheer scale of the conflict makes the exact number uncertain but it is likely that well over 200,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during the war.

As in Britain, the motivation of the men and women who volunteered – and all, of course, were volunteers as conscription was never, in the end, introduced in Ireland – would have been many and varied. For some the motivation to join up was as old as history – because in straightened times it was a means by which impoverished young men could get three square meals a day, clothes on their back and a roof over their heads. That’s not solely an Irish phenomenon. It was true for much of Britain and her empire. And I’m sure for the Continental Powers too.

Others may have joined up out of a sense of duty or in search of adventure or to escape from the crushing tedium and lack of horizons that was otherwise their poor lot in life. Some may have done so in order to defend the neutrality of a small, catholic country – Belgium. And many nationalists would have shared John Redmond’s vision that the war provided an opportunity to, “Win for our country the most inestimable treasure to be obtained, in creating a free and united Ireland – united North and South, Catholic and Protestant”.

Shared Commemoration

But it is, of course, a matter of record that the history of the Irish Republic meant that – motivations aside – commemoration of the fallen in the aftermath of 1918 was a more complex affair than it was in Britain. Conflicting emotions meant that Remembrance Sunday in Dublin was itself riven with tension – certainly throughout the 1920s and 30s.

Eamon Gilmore, Deputy Prime Minister of Ireland, this month, at the launching of a new website giving the biographical details of the Irish First World War dead, put it this way: “The First World War in Ireland was seen for many years as a divisive part of our troubled legacy. And because of this, there was a tendency to avoid any interrogation of Irish involvement.’’ However, we have learnt that contending with the past, as we have done over a number years in relation to Ireland’s role and contribution, has brought with it great opportunities to recognise in our reflections on the war our common humanity, our common cause, and our common heritage.”

I very much agree. And we should not devalue our Remembrance of British and Irish servicemen because of perceptions of the futility of the First World War or because of what Mr Gilmore calls Ireland’s troubled legacy. That is not to say such propositions are unimportant or binary. In some minds there is still a tension between this year’s commemoration being seen as a rededication of peace on the one hand and it being a more overt recognition that the dead of the First War perished ‘so that we might be free’ – with all the historical meaning that that phrase entails.

But when all is said and done, a shared respect for the sacrifices that those British and Irish troops made is a perspective on which I believe we can all agree. It is, as it were, our common starting point on a journey.

Shared Suffering

If shared involvement is a key aspect of how we look back at the events unfurling in 1914 so was the scale of the suffering. It was suffering on an unimaginable, though not unprecedented, scale. Exact numbers can never be established, of course, given the industrial scale of the slaughter and the long shadow cast by the war. A conservative estimate would be that at least 30,000 Irishmen lost their lives as a result of their service. This gives a casualty rate of 14%, in line with that experienced by British Forces overall.

And the sense of loss among the families of the dead and afflicted was the same in Dublin, Belfast, London, Glasgow or Cardiff. With the support of the Irish government, that service and the sacrifice of those who died will be recognised further with the erection by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission of a Cross of Sacrifice at Glasnevin Cemetery later this year. I have visited Glasnevin and know full well the totemic significance of what is proposed in the lee of Daniel O’Connell’s tomb.

Many of the Irishmen to be commemorated at Glasnevin served in the 10th, 16th and 36th Divisions of the British Army and saw action in the war’s signature battles. Tens of thousands served in other units, in the Royal Navy and in the nascent Royal Air Force. And it was of course as part of the advance of Irish troops of the 16th and 36th divisions at Messines in June 1917 that the Irish Nationalist MP for East Clare, Major Willie Redmond, lost his life. As an ardent home-ruler he believed his war service would help bring about north-south reconciliation.

Writing to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in 1916, he said “It would be a fine memorial to the men who have died so splendidly if we could, over their graves, build up a bridge between North and South. I have been thinking a lot about this lately in France – no one could help doing so when one finds that the two sections from Ireland are actually side by side holding the trenches!”

Soldiers from Munster

And since we are in Cork today you’ll perhaps allow me to dwell for a moment on the particular contributions that men from Munster made. Men who, before Independence, had had a long history of service in the British Army and, let us not forget, the Royal Navy in Cork. These men were to see especially active service in the British Armed Forces during the First World War. Indeed the actions of the men from Munster are able to articulate my proposition much better than I can as a politician.

The Royal Munster Fusiliers drew particularly from this area and sons of the province served with great distinction on the Western Front. Men like Martin Doyle, a Royal Munster Fusilier, though one from County Wexford, who was awarded the Victoria Cross in 1918 and later joined the IRA in the war of independence before fighting for the pro-treaty cause in the civil war.

Michael O’Leary of the Irish Guards from Inchigeela, County Cork, another winner of the Victoria Cross and one of the best known Cork personalities of the period, about whose deeds of valour George Bernard Shaw wrote a play. He re-joined the British army to fight in the Second World War, eventually being discharged in 1945 on medical grounds having reached the rank of Major.

And Tom Barry from Killorglin County Kerry, the Royal Artillery gunner who served for over three years in the British army before his second career in the IRA in the war of independence and later on the anti-treaty side in the civil war.

The point is that these three men were not only brave and accomplished soldiers, their personal stories show how complicated the politics and allegiances of the time were. It is exactly this complexity that should lead us to the conclusion that, in Ireland’s decade of commemorations, we should remember with respect the sacrifice of all of that generation, from whichever traditions or perspectives they fought. One hundred years on from those tumultuous events, our passions are cooler and our appraisal can be more nuanced, objective and multi-faceted. A hundred years gives us that space.

In her visit to Ireland in 2011, Her Majesty the Queen laid a laurel wreath at the Garden of Remembrance in Dublin in honour of those who had died in the cause of Irish freedom. That, of course, very much included a generation of Irishmen and women, among whom were some who returned from fighting in British uniform in the First World War to fighting against those in British uniform in the war of independence.

As historians, you will delve into this complexity in much greater detail than I can. And you will, no doubt, have your debates and differences as you seek to shed light on the events of the time. When David Cameron announced last year our approach to the First World War centenary, he said that commemorations would be based on three themes – remembrance, youth and education. He was clear this would be commemoration, not a celebration.

In the UK, we will hold national events to mark the start and end of the war and to commemorate its great battles and campaigns – in all of which Irishmen took part. Those national events will have a Commonwealth look and feel to them – or rather I should say an Ireland and Commonwealth look and feel to them – reflecting the reality of the time. And they will also include countries who were not our allies then but who are now valued partners and friends.

Let me say a word about remembrance. Remembrance is not the same as recollection. How can it be since none of us here can recollect the events of 1914. Remembrance is the process of honouring the fallen, bringing to mind their suffering and resolving to strive for better. The objective is to achieve a richer, deeper and more reflective legacy of the war. I have argued there will be many differing interpretations of the war. We may disagree with some of them. But it is not the role of government to prescribe. Our role is to lead and encourage. It is emphatically not the place of government to be handing down approved versions of history.

Research carried out for an NGO called British Future found that 77% of the public see the First World War centenary as an opportunity for reconciliation.The British government very much agrees. Reconciliation does not mean seeking to bend historical inquiry to fit its purpose. Quite the contrary. The goal of reconciliation is served by as open-minded an approach to the past as possible.

But as a British Government minister, my interest is not only in achieving an accurate version of the past and in facilitating exploration of the causes, conduct and consequences of the war, it also lies in finding a way to commemorate events to help heal historic divisions and promote reconciliation between our countries and our peoples. As President Higgins said last week: “We need new myths that not only carry the burden of history but fly from it and make something new.”

If we manage to promote reconciliation and friendship in the course of commemorating the events of 100 years ago, we will have been true to our present and to our past. To our present, because the modern relationship between Britain and Ireland is based on respect, friendship and cooperation. To our past, because so many hoped that the experience of shared sacrifice in a common endeavour would bring people together.

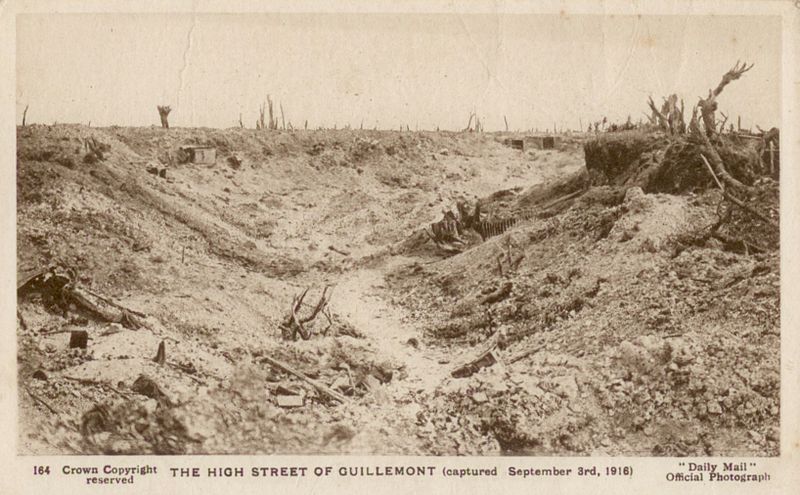

Tom Kettle, the Irish nationalist politician, poet and British soldier, famously said: “Used with the wisdom that is sown in tears and blood, this tragedy of Europe may be and must be the prologue to the two reconciliations of which all statesmen have dreamed, the reconciliation of Protestant Ulster with Ireland, and the reconciliation of Ireland with Great Britain.” Sadly, Lieutenant Kettle’s death, leading his men in the successful capture of the village of Guinchy on the Somme in 1916, and the wholesale sowing of blood he referred to, did not, in the years following the war, promote the cause of reconciliation in which he so fervently believed.

But what a magnificent tribute it would be – to him and to those who fought with him from Ireland, north and south, and from Great Britain – to commemorate the war in a manner commensurate with those two reconciliations. And that is the approach being taken by both the British and Irish governments. I applaud the example set by the visit by the Taoiseach and David Cameron to Flanders last month honouring our war dead together.

There will be many other opportunities for members of both our governments – and indeed our publics – to stand shoulder to shoulder in remembrance in the coming years. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we shall remember them – all of them.

Conclusion

In closing I might turn to an article that I saw in the Irish Independent just a few days ago. It concerned Private John Mulalley from County Meath who joined the Connaught Rangers before dying in Flanders early in the War. Private Mullaley is listed at the Menin Gate in Ypres alongside more than 54,000 officers and men who lost their lives in Flanders and who have no known grave. His niece – now 80 – reflected on the difficulties when she was growing up of discussing at home Uncle John’s service. But she concluded by welcoming the fact that time has allowed the sacrifices of the Irish dead to be discussed freely and for those who perished to be remembered.And if in doing so we can draw our two countries together just a little bit more, we will have honoured our dead with a legacy of peace.

Ladies and Gentlemen

Thank you.