Dalriada and the Epidian and Robogdian Pretani

Peoples of Northern Britain according to Ptolemy’s map

The Epidian Cruthin (Pretani) or Epidii (Greek Επίδιοι) were an ancient British people, known from a mention of them by Ptolemy the geographer c. 150.The name Epidii includes the Gallo-Brittonic root epos, meaning horse (Compare with Old Gaelic ech). It may, perhaps, be related to the Horse-goddess Epona. They inhabited the modern-day regions of Argyll and Kintyre, as well as the islands of Islay and Jura, from which my great-granny Lambey was sprung. They were originally non European and then Picto/Brittonic or Pretanic in speech, although later Gaelicised to become part of the heartland of the kingdom of Dalriada (Dál Riata).

Dalriada was founded by Gaelic-speaking people from Ulster, including Robogdian Cruthin (Pretani), who eventually Gaelicised the west coast of Pictland, according to the Venerable Bede, by a combination of force and treaty. The indigenous Epidian people however remained substantially the same and there is no present archaeological evidence for a full-scale migration or invasion. The inhabitants of Dalriada are often referred to as Scots (Latin Scotti), a name originally used by Roman and Greek writers for the Irish who raided Roman Britain. Later it came to refer to Gaelic-speakers in general, whether from Ireland or elsewhere.The name Dál Riata is derived from Old Gaelic. Dál means “portion” or “share” (as in “a portion of land”) and Riata or Riada is believed to be a personal name. Thus, Riada’s portion.

In Argyll Dalriada consisted initially of three kindreds; Cenél (Clan) Loairn (kindred of Loarn) in north and mid-Argyll, Cenél nÓengusa (kindred of Óengus) based on Islay and Cenél nGabráin (kindred of Gabrán) based in Kintyre; a fourth kindred, Cenél Chonchride in Islay, was seemingly too small to be deemed a major division. By the end of the 7th century another kindred, Cenél Comgaill (kindred of Comgall), had emerged, based in eastern Argyll. The Lorn and Cowal districts of Argyll take their names from Cenél Loairn and Cenél Comgaill respectively, while the Morven district was formerly known as Kinelvadon, from the Cenél Báetáin, a subdivision of the Cenél Loairn.

The kingdom reached its height under Áedán mac Gabráin (r. 574–608), but its growth was checked at the Battle of Degsastan in 603 by Æthelfrith of Northumbria. Serious defeats in Ireland and Scotland in the time of Domnall Brecc (d. 642) ended Dál Riata’s “golden age”, and the kingdom became a client of Northumbria, then subject to the Picts (Caledonian Cruthin or Pretani). There is disagreement over the fate of the kingdom from the late eighth century onwards. Some scholars have seen no revival of Dalriada after the long period of foreign domination (after 637 to around 750 or 760), while others have seen a revival of Dalriada under Áed Find (736–778), and later Kenneth Mac Alpin (Cináed mac Ailpín, who is claimed in some sources to have taken the kingship there in c.840 following the disastrous defeat of the Pictish army by the Danes): some even claim that the kingship of Fortriu was usurped by the Dalriadans several generations before MacAlpin (800–858). The kingdom’s independence ended in the Viking Age, as it merged with the lands of the Picts to form the Kingdom of Alba.

Among the royal centres in Dalriada, Dunadd, which we have visited with our Dalaradia organisation, appears to have been the most important. It has been partly excavated, and weapons, quern-stones and many moulds for the manufacture of jewellery were found in addition to fortifications. Other high-status material included glassware and wine amphora from Gaul, and in larger quantities than found elsewhere in Britain and Ireland. Lesser centres included Dun Ollaigh, seat of the Cenél Loairn kings, and Dunaverty at the southern end of Kintyre, in the lands of the Cenél nGabráin. The main royal centre in Ulster appears to have been at Dunseverick (Dún Sebuirge).

There are no written accounts of pre-Christian Dalriada, the earliest records coming from the chroniclers of Iona and Irish monasteries. Adomnán’s Life of St Columba implies a Christian Dalriada Whether this is trueor not cannot be known. The figure of Columba looms large in any history of Christianity in Dalriada. Adomnán’s Life, however useful as a record, was not intended to serve as history, but as hagiography. We are fortunate that the writing of saints’ lives in Adomnán’s day had not reached the stylised formulas of the High Middle Ages, so that the Life contains a great deal of historically valuable information. It is also a vital linguistic source indicating the distribution of Gaelic and P-Celtic or Brittonic placenames in northern Scotland by the end of the 7th century. It famously notes Columba’s need for a translator when conversing with an individual on Skye. This evidence of a non-Gaelic language is supported by a sprinkling of Brittonic placenames on the remote mainland opposite the island.

Columba’s founding Iona within the bounds of Dalriada ensured that the kingdom would be of great importance in the spread of Christianity in northern Britain, not only to Pictland, but also to Northumbria, via Lindesfarne, to Mercia, and beyond. Although the monastery of Iona belonged to the Cenel Conaill of the Venniconian Cruthin of modern Donegal, and not to Dalriada, it had close ties to the Cenél nGabráin, (ties which may make the annals less than entirely impartial), in the territory of the Cenél Loairn, and was sufficiently important for the death of its abbots to be recorded with some frequency. Applecross, probably in Pictish territory for most of the period, and Kingart on Bute, are also known to have been monastic sites, and many smaller sites, such as on Eigg and Tiree, are known from the annals. In Ireland, Armoy was the main ecclesiastical centre associated with Saint Patrick and with Saint Olcán, said to have been first bishop at Armoy. An important early centre, Armoy later declined, overshadowed by the monasteries at Movilla (Newtownards) and the greatest of all, Bangor. The importance of Bangor cannot be over-estimated, yet it has been neglected due to the combined influences of Irish, Scottish and English nationalist academics.

The history of Dalriada, while unknown before the middle of the 6th century, and very unclear after the middle of the 8th century, is relatively well recorded in the intervening two centuries, There is no doubt that Ulster Dalriada was a lesser kingdom of Ulaid. The Kingship of Ulster was dominated by the Dal Fiatach of North Down and Ards and contested by the Cruthin kings of Dalaradia, who maintained that they, and not the Dal Fiatach, were the true Ulstermen.

In 575, Columba fostered an agreement between Áedán mac Gabráin and his kinsman Áed mac Ainmuirech of the Cenél Conaill at Druim Cett. This alliance was likely precipitated by the conquests of the Dál Fiatach king Baetan mac Cairill. Báetán died in 581, but the Ulaid kings did not abandon their attempts to control Dalriada.The kingdom of Dalriada reached its greatest extent in the reign of Áedán mac Gabráin. It is said that Áedán was consecrated as king by Columba. If true, this was one of the first such consecrations known. As noted, Columba brokered the alliance between Dalriada and his kindred ,the Venniconian Cruthin of Cenél Conaill , of the so-called “Northern Uí Néill”.

This pact was successful, first in defeating Báetan mac Cairill, then in allowing Áedán to campaign widely against his neighbours, as far afield as Orkney and the Pictish lands of the Maeatae, on the River Forth. Áedán appears to have been very successful in extending his power, until he faced the Bernician king Æthelfrith at Degsastan c. 603. Æthelfrith’s brother was among the dead, but Áedán was defeated, and the Bernician kings continued their advances in southern “Scotland”. Áedán died c. 608 aged about 70. Dalriada did expand to include Skye, possibly conquered by Áedán’s son Gartnait. It appears, although the original tales are lost, that Fiachnae mac Báetáin (d. 626), Dalaradian King of Ulster, was overlord of both parts of Dalriada. Fiachnae campaigned against the Northumbrians, and besieged Bamburgh, and the Dalriadans will have fought in this campaign.

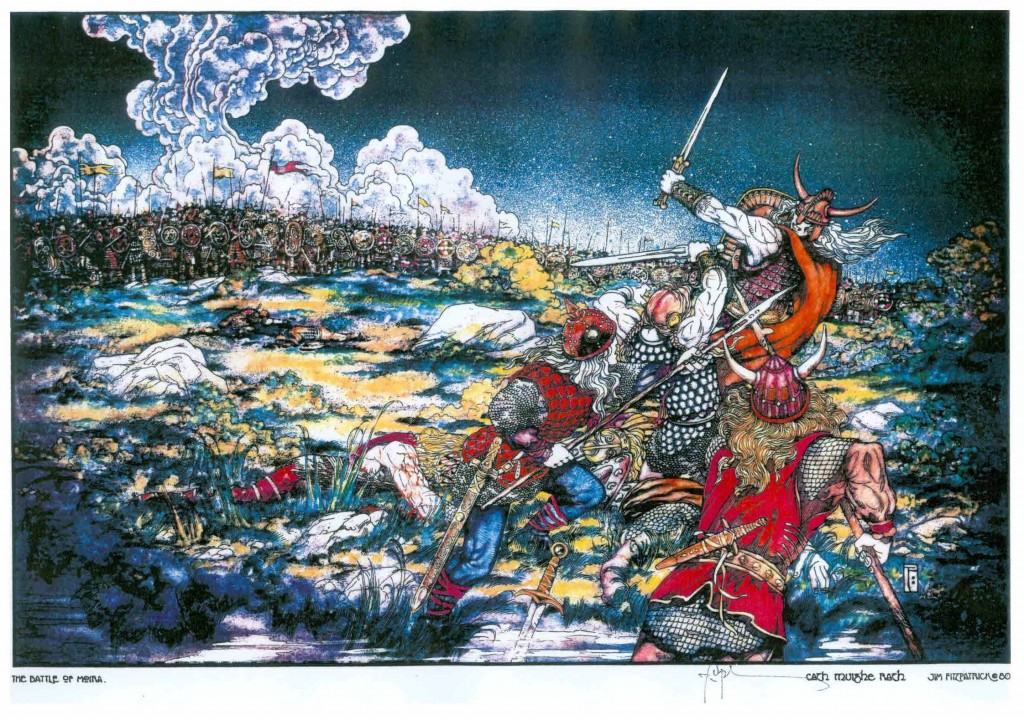

Dalriada remained allied with the “Northern Uí Néill” until the reign of Domnall Brecc, who reversed this policy and allied with Congal Cláen of the Dalaradians. Domnall joined Congal in a campaign against Domnall mac Áedo of the Cenél Conaill, the son of Áed mac Ainmuirech The outcome of this change of allies was defeats for Domnall Brecc and his allies on land at Mag Rath (Moira, County Down) and at sea at Sailtír, off Kintyre, in 637. This, it was said, was divine retribution for Domnall Brecc turning his back on the alliance with the kinsmen of Columba. Domnall Brecc’s policy appears to have died with him in 642, at his final, and fatal, defeat by Eugein map Beli of Alt Clut at Strathcarron, for as late as the 730s, armies and fleets from Dalriada fought alongside the “Uí Néill”.

Yr Hen Ogledd (The Old North)

Yr Hen Ogledd (The Old North) is a Brittonic “Welsh” or Cymric term which refers to those parts of what is now northern “England” and southern “Scotland” in the years between 500 and the Viking invasions of c. 800, with particular interest in the Brittonic or Old British-speaking peoples who lived there. Until recently, knowledge of the Old North has been suppressed by the partisan nationalist academic elites of Ireland, Scotland and England, but teaching our people about it through the internet will be an essential part of the modern Ulster and Appalachian cultural revolution.

Places in the Old North, the Middle Lands, that are mentioned as kingdoms in the literary and historical sources include:

- Alt Clut or Ystrad Clud – a kingdom centred at what is now Dumbarton in “Scotland”. Later known as the Kingdom of Strathclyde, it was one of the best attested of the northern British kingdoms. It was also the last surviving, as it operated as an independent realm into the 11th century before it was finally absorbed by the Kingdom of Scotland and its ecclesiatical centre of Govan superceded by Glasgow.

- Elmet – centred in western Yorkshire in northern “England”. It was located south of the other northern British kingdoms, and well east of present-day Wales, but managed to survive into the early 7th century.

- Gododdin – a kingdom in what is now southeastern Scotland and northeastern England, the area previously noted as the territory of the Votadini. They are the subjects of the poem Y Goddodin, which memorialises an illfated foray by an army raised by the Gododdin on the English of Bernicia.

- Rheged – a major kingdom in Galloway and Carrick that may have included parts of present-day Cumbria, though its full extent is unknown. It may have covered a vast area at one point, as it is very closely associated with its king Urien, whose name is tied to places all over northwestern Britain.

Several regions are mentioned in the sources, assumed to be notable regions within one of the kingdoms if not separate kingdoms themselves:

- Aeron – a minor kingdom mentioned in sources such as Y Gododdin, which gave its name to Ayrshire in southwest Scotland. It is frequently associated with Urien of Rheged and may have been part of his realm.

- Calchfynydd (“Chalkmountain”) – almost nothing is known about this area, though it was likely somewhere in the Hen Ogledd, as an evident ruler, Cadrawd Calchfynydd, is listed in the Bonedd Gwyr y Gogledd. William Forbes Skene suggested an identification with Kelso (formerly Calchow) in the Scottish Borders.

- Eidyn – this was the area around the modern city of Edinburgh then known as Din Eidyn (Fort of Eidyn). It was closely associated with the Gododdin kingdom. Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson argued strongly that Eidyn referred exclusively to Edinburgh, but other scholars have taken it as a designation for the wider area.] The name survives today in toponyms such as Edinburgh, Dunedin, and Carriden (from Caer Eidyn), located fifteen miles to the west. Din Eidyn was besieged by the English in 638 and was under their control for most of the next three centuries.

- Manau Gododdin – the coastal area south of the Firth of Forth, and part of the territory of the Gododdin. The name survives in Slamannan Moor and the village of Slamannan in Stirlingshire. This is derived from Sliabh Manann, the ‘Moor of Manann’. It also appears in the name of Dalmeny, some 5 miles northwest of Edinburgh, and formerly known as Dumanyn, assumed to be derived from Din Manann. The name also survives north of the Forth in Pictish Manaw as the name of the burgh of Clackmannan and the eponymous county of Clackmannanshire, derived from Clach Manann, the ‘stone of Manann’, referring to a monument stone located there.

- Novant – a kingdom mentioned in Y Gododdin, presumably related to the Novantae people of southwestern Scotland.

- Regio Dunutinga – a minor kingdom or region in North Yorkshire mentioned in the Life of Wilfrid . It was evidently named for a ruler named Dunaut, perhaps the Dunaut ap Pabo known from the genealogies. Its name may survive in the modern town of Dent, Cumbria.

Kingdoms that are not descibed by the academic elite as part of the Old North but are part of its history include:

- Dalriada (Dál Riata) – Alhough this was a Gaelic-speaking kingdom in early Mediæval times, its people were indigenous Epidian Cruthin (Pretani) and the family of Áedán mac Gabráin of Dalriada appears in the Bonedd Gwýr y Gogledd (The Descent of the Men of the North).

- English Northumbria and its predecessor states, Bernicia and Deira, which engulfed the Middle Kingdoms.

- The Caledonian Cruthin or Pretani Kingdom of Pictavia.

- Bryneich – this is the Brittonic name for the English kingdom of Bernicia and was the pre-Anglo-Saxon Brittonic kingdom in this area.

- Deifr or Dewr – this was the Britttonic name for the English Deira, a region between the River Tees and the Humber. The name is of Brittonic origin, and as with Bryneich, represented the earlier Brittonic kingdom.

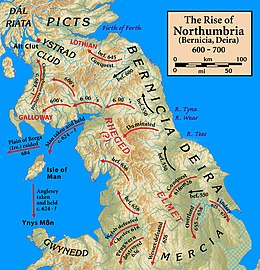

The Rise of Northumbria.

Northumbria was originally composed of the union of the two independent Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Bernicia, the former Britonnic kingdom of Bryneich and Deira, the former Britonnic kingdom of Deifr or Dewr. Bernicia covered lands north of the Tees, while Deira corresponded roughly to modern-day Yorkshire, absorbing the Britonnic Kingdom of Elmet. Bernicia and Deira were first united by Aethelfrith, a king of Bernicia, who conquered Deira around the year 604. He was defeated and killed around the year 616 in battle at the River Idle by Raedwald of East Anglia, who installed Edwin, the son of Aella, a former king of Deira, as king.

Edwin, who accepted Christianity in 627, soon grew to become the most powerful king in England. He was recognised as Bretwealda or Ruler of all Britain and its islands, including Ireland, the original Islands of the Pretani, and he conquered the Isle of Man amd Gwynedd in Northern Wales. He was, however, himself defeated by an alliance of the exiled king of Gwynedd, Cadwallon ap Cadfan and Penda, king of Mercia, at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633.

After Edwin’s death, Northumbria was split between Bernicia, where Eadfrith, a son of Aethelfrith, took power, and Deira, where a cousin of Edwin, Osric, became king. British Cumbria tended to remain a country frontier with the Britons. Both of these rulers were killed during the year that followed, as Cadwallon continued his devastating invasion of Northumbria. After the murder of Eanfrith, his brother, Oswald, backed by warriors sent by Domnall Brecc of Dalriada (Dál Riata), defeated and killed Cadwallon at the Battle of Heavenfield in 634.

Oswald expanded his kingdom considerably. He incorporated Gododdin lands northwards up to the Firth of Forth and also gradually extended his reach westward, encroaching on the remaining British speaking kingdoms of Rheged and Strathclyde. Thus, Northumbria became not only part of the far north of modern “England”, but also covered much of what is now the south-east of modern “Scotland”. King Oswald re-introduced Christianity to the Kingdom by appointing St Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona to convert his people. This led to the introduction of the practices of “Celtic” Christianity and a monastery was established on Lindesfarne.

War with Mercia continued, however. In 642, Oswald was killed by the Mercians under Penda at the Battle of Maserfield. In 655, Penda launched a massive invasion of Northumbria, aided by the sub-king of Deira, Aethelwald, but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of an inferior force under Oswiu , Oswald’s successor, at the Battle of Winwaed. This battle marked a major turning point in Northumbrian fortunes: Penda died in the battle, and Oswiu gained supremacy over Mercia, making himself the most powerful king in England.

In the year 664 the Synod of Witby was held to discuss the controversy regarding the timing of the Easter festival. Much dispute had arisen between the practices of the “Celtic” church in Northumbria and the beliefs of the Roman church. Eventually, Northumbria was persuaded to move to the Roman practice and the Celtic Bishop Colman of Lindesfarne returned to Iona.

Northumbria lost control of Mercia in the late 650s, after a successful revolt under Penda’s son Wulfhere, but it retained its dominant position until it suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Picts at the Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685; Northumbria’s king, Ecgfrith (son of Oswiu), was killed, and its power in the north was gravely weakened. The peaceful reign of Aldfrith, Ecgfrith’s half-brother and successor, did something to limit the damage done, but it is from this point that Northumbria’s power began to decline, and chronic instability followed Aldfrith’s death in 704.

In 867 Northumbria became the northern kingdom of the Danelaw, after its conquest by the brothers Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless who installed an Englishman, Ecgberht, as a puppet king. Despite the pillaging of the kingdom, Viking Rule brought lucrative trade to Northumbria, especially at their capital York. The kingdom passed between English, Norse and Norse-Gaelic kings until it was finally absorbed by King Eadred after the death of the last independent Northumbrian monarch, Erik Bloodaxe, in 954.

After the English regained the territory of the former kingdom, Scots invasions reduced Northumbria to an earldom stretching from the Humber to the Tweed. Northumbria was disputed between the emerging kingdoms of England and Scotland. The land north of the Tweed was finally ceded to Scotland in 1018 as a result of the Battle of Carham. Yorkshire and Northumberland were first mentioned as separate in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1065. William the Bastard became king of England in 1066. He realised he needed to control Northumbria, which had remained virtually independent of the Kings of England, to protect his kingdom from Scottish invasion. In 1067, William appointed Copsi (sometimes Copsig) as Earl. However, just five weeks into his reign as earl, Copsi was murdered by Osulf II of Bamburgh.

To acknowledge the remote independence of Northumbria and ensure England was properly defended from the Scots, William gained the allegiance of both the Bishop of Durham and the Earl and confirmed their powers and privileges. However, anti-Norman rebellions followed. William therefore attempted to install Robert Comine, a Norman Noble noble, as the Earl of Northumbria, but before Comine could take up office, he and his 700 men were massacred in the city of Durham. In revenge, the now “Conqueror” led his army in a bloody raid into Northumbria, an event of ethnic cleansing that became known as the harrying of the North. Ethelwin, the Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Durham, tried to flee Northumbria at the time of the raid, with Northumbrian treasures. The bishop was subsequently caught, imprisoned, and later died in confinement; his seat was left vacant.

Rebellions continued, and William’s son William Rufus decided to partition Northumbria. William of St Carilef was made Bishop of Durham, and was also given the powers of Earl for the region south of the rivers Tyne and Derwent, which became the County Palatine of Durham.The remainder, to the north of the rivers, became Nothhumberland, where the political powers of the Bishops of Durham were limited to only certain districts, and the earls continued to rule as clients of the English throne. The city of Newcasltle was founded by the Normans in 1080 to control the region by holding the strategically important crossing point of the river Tyne.

The flag of the kingdom was “a banner made of gold and purple” (or red), first recorded in the 8th century as having hung over the shrine of King Oswald. This was later interpreted as vertical stripes. A modified version (with broken vertical stripes) can be seen in the coat of arms and flag used by Northumberland County Council.

Northumbria during its “golden age” was the most important centre of religious learning and arts in the British Isles. Initially the kingdom was evangelised by Irish monks from the “Celtic” Church, based at Iona in modern Scotland, which led to a flowering of monastic life. Lindesfarne on the east coast was founded from Iona by Saint Aidan in about 635, and was to remain the major Northumbrian monastic centre, producing figures like Wilfrid and Saint Cuthbert. The nobleman Benedict Biscop had visited Rome and headed the monastery at Canterbury in Kent and his twin-foundation Monkwearmouth -Jarrow Abbey added a direct Roman influence to Northumbrian culture, and produced figures such as Coelfrith and Bede.

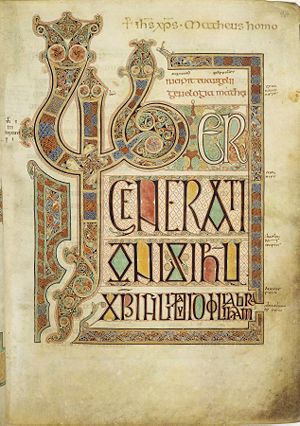

Northumbria played an important role in the formation of Insular Art, a unique style combining Anglo-Saxon, Pictish, Byzantine and other elements, producing works such as the Lindesfarne Gospels. St Cuthbert Gosplel, the Ruthwell Cross and Bewcastle Cross, and later the Book of Kells, which was probably created at Iona. After the Synod of Whitby in 664 Roman church practices officially replaced the “Celtic” ones but the influence of the “Celtic style continued, the most famous examples of this being the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Venerable Bede (673–735) wrote his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed in 731) in Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, and much of it focuses on the kingdom. The devastating Viking raid on Lindisfarne in 793 marked the beginning of a century of Viking invasions that severely checked all Anglo-Saxon culture, and heralded the end of Northumbria’s position as a centre of influence, although in the years immediately following confident works like the Easby Cross were still being produced.

Northumbria has its own check or tartan, which is similar to many ancient tartans (especially those from Northern Europe, such as one found near Falkirk and those discovered in Jutland that date from Roman times (and even earlier). Modern Border Tartans are almost invariably a bold black and white check, but historically the light squares were the yellowish colour of untreated wool, with the dark squares any of a range of dark greys, blues, greens or browns; hence the alternative name of “Border Drab”. At a distance the checks blend together making the fabric ideal camouflage for stalking game.

The most persistent influence of Northumbria, however, is its language. From Old Northumbrian English developed modern Geordie and other variants, i.e. Northern (north of the Rver Coquet), Western (from Allendale through Hexham up to Kielde), Southern or Pitmatic (the mining towns such as Ashington and much of Durham), Mackem (Wearside), Smoggie (Teeside) and possibly also Tyke (Yorkshire). It is spoken mainly if not exclusively in the modern day counties of Northumberland and Durham. Whilst all sharing similarities to the more famous Geordie dialect and most of the time not distinguishable by non-native speakers, there are a few differences between said variants not only between them and Geordie but also each other. Yet the most prominent derivative of Old Northumbian English is modern Scots and its variant Ulster-Scots, also known as Scotch-Irish or Ullans. The latter term I created as a neologism to differentiate the language from Ulster-Scots or Scotch Irish traditions and it has found its way into the Belfast Agreement through David Trimble and David Campbell of the Ulster Unionist Party.

The Border Reivers

The Border Reivers were the descendants of the Brittonic Middle Kingdoms along the Anglo-Scottish border from the late 13th century to the beginning of the 17th century. Their ranks consisted of both Scottish and English families, and they raided the entire border country without regard to Scottish or English “nationality”. Their heyday was perhaps in the last hundred years of their existence, during the time of the Stewart Kings in Scotland and the Tudor Dynasty in England. The Norman kingdoms of Scotland and England were frequently at war during the late Middle Ages, divided as they were artificially by the Roman Wall of Hadrian. During these wars, the livelihood of the people on the borders was devastated by the contending armies. Even when the countries were not at war, tension remained high, and royal authority in either kingdom was often weak. The uncertainty of existence meant that communities or people kindred to each other would seek security through their own strength and cunning, and improve their livelihoods at their nominal enemies’ expense. Loyalty to a feeble or distant monarch and reliance on the effectiveness of the law usually made people a target for depredations rather than conferring any security.

There were other factors which promoted theirmode of living. Among them was the survival in the Borders of the inheritance system of gavelkind, by which estates were divided equally between all sons on a man’s death, so that many people owned insufficient land to maintain themselves. Also, much of the border region is mountainous or open moorland, unsuitable for arable farming but good for grazing. Livestock was easily rustled and driven back to raiders’ territory by mounted reivers who knew the country well. The raiders also often removed “insight,” easily portable household goods or valuables, and took prisoners for ransom.

The attitudes of the English and Scottish governments towards the border families alternated between indulgence or even encouragement, as these fierce families served as the first line of defence against invasion from the other side of the border, and draconian and indiscriminate punishment when their lawlessness became intolerable to the authorities.

The popular story handed down within reiver families is that from earliest times, reivers would visit the homesteads prior to wars or invasions and remove the cattle and items of value to a place of safety. Lords and Wardens unable to guarantee their masters’ supply lines would claim wrongdoing by ruffians and broken men. It is easy to conjecture that this attitude of defiance to authority would grow into outright lawlessness.

“Reive” is an early English word for “to rob”, from the Northumbrian and Scots verb reifen from the Old English rēafian, and thus related to the archaic Standard English verb reave (“to plunder”, “to rob”), and to the modern English word “ruffian”.

The reivers were both English and Scottish and raided both sides of the border impartially, so long as the people they raided had no powerful protectors and no connection to their own kin. Their activities, although usually within a day’s ride of the Border, extended both north and south of their main haunts. English raiders were reported to have hit the outskirts of Edinburgh, and Scottish raids were known as far south as Yorkshire. The main raiding season ran through the early winter months, when the nights were longest and the cattle and horses fat from having spent the summer grazing. The numbers involved in a raid might range from a few dozen to organised campaigns involving up to three thousand riders.

When raiding, or riding, as it was termed, the Reivers rode light on hardy nags or ponies renowned for the ability to pick their way over the boggy moss lands.The original dress of a shepherd’s plaid was later replaced by light armour such as Brigantines or jacks of plaite (a type of sleeveless doublet into which small plates of steel were stitched), and a metal helmet such as a burgonet or morion; hence their nickname of the steel bonnets. They were armed with a lance and small shield, and sometimes also with a longbow, or a light crossbow known as a “latch”, or later on in their history with one or more pistols. They invariably also carried a sword and dirk.

As soldiers, the Border Reivers were considered among the finest light cavalry in all of Europe. After meeting one Reiver (the Bold Buccleugh), Queen Elizabeth I is quoted as having said that “with ten thousand such men, James VI could shake any throne in Europe.” Reivers served as mercenaries, or were forced to serve in English and Scots armies in the Low Countries and in Ireland. Such service was often handed down as a penalty in lieu of that of death upon their families.

Reivers fighting as levied soldiers played important parts at the battles of Flodden Field and Solway Moss. When fighting as part of larger English or Scottish armies, Borderers were difficult to control as many had relatives on both sides of the border, despite laws forbidding international marriage. They could claim to be of either nationality, describing themselves as Scottish if forced, English at will and a Reiver or Old British by grace of blood. They were badly-behaved in camp, frequently plundered for their own benefit instead of obeying orders, and there were always questions about how loyal they were. At battles such as Ancrum Moor in Scotland in 1545, borderers changed sides in mid-battle, to curry favour with the likely victors, and at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547, an observer (William Patten) noticed that the Scottish and English borderers were talking to each other in the midst of battle, and on being spotted put on a show of fighting.

The inhabitants of the Borders had to live in a state of constant alert, and for self-protection, they built fortified tower houses.

In the very worst periods of warfare, people were unable to construct more than crude turf cabins, the destruction of which would be little loss. When times allowed however, they built houses designed as much for defence as shelter. The Bastle House was a stout two-storeyed building. The lower floor was used to keep the most valuable livestock and horses. The upper storey housed the people, and often could be reached only by an external ladder which was pulled up at night or if danger threatened. The stone walls were up to 3 feet (0.91 m) thick, and the roof was of slate or stone tiles. Only narrow arrow slits provided light and ventilation.

Such dwellings could not be set on fire, and while they could be captured, for example by smoking out the defenders with fires of damp straw or using scaling ladders to reach the roof, they were not worth the time and effort. If necessary, they could be temporarily abandoned and stuffed full of smouldering turf to prevent an enemy (such as a government army) destroying them with gunpowder.

Peel towers (also spelled Pele Towers) were usually three-storeyed buildings. They were usually constructed specifically for defensive purposes by the authorities, or for prestigious individuals such as the heads of clans. Smailholm Tower is one of many surviving Peel towers.

Peel towers and bastle houses were often surrounded by a stone wall known as a barmkin, inside which cattle and other livestock were kept overnight.

During periods of nominal peace, a special body of customary law, known as Border Law, grew up to deal with the situation. Under Border Law, a person who had been raided had the right to mount a counter-raid within six days, even across the border, to recover his goods. This Hot Trod had to proceed with “hound and horne, hew and cry”, making a racket and carrying a piece of burning turf on a spear point to openly announce their purpose, to distinguish themselves from unlawful raiders proceeding covertly. They might use a sleuth hound (also known as a “slew dogge”) to follow raiders’ tracks. These dogs were valuable, and part of the established forces (on the English side of the border, at least). Any person meeting this counter-raid was required to ride along and offer such help as he could, on pain of being considered complicit with the raiders. The Cold Trod mounted after six days required official sanction. Officers such as the Deputy Warden of the English West March had the specific duty of “following the trod”.

Both sides of the border were divided into Marches, each under a March Warden. The March Wardens’ various duties included the maintenance of patrols, watches and garrisons to deter raiding from the other kingdom. On occasions March Wardens could make Warden Roades to recover loot, and to make a point to raiders and officials.

The March Wardens also had the duty of maintaining such justice and equity as was possible. The respective kingdoms’ March Wardens would meet at appointed times along the border itself to settle claims against people on their side of the border by people from the other kingdom. These occasions, known as “Days of Truce”, were much like fairs, with entertainment and much socialising. For Reivers it was an opportunity to meet (lawfully) with relatives or friends normally separated by the border. It was not unknown for violence to break out even at such truce days.

March Wardens (and the lesser officers such as Keepers of fortified places) were rarely effective at maintaining the law. The Scottish Wardens were usually borderers themselves, and were complicit in raiding. They almost invariably showed favour to their own kindred, which caused jealousy and even hatred among other Scottish border families. Many English officers were from southern counties in England and often could not command the loyalty or respect of their locally-recruited subordinates or the local population. Local officers such as Sir John Forster, who was Warden of the Middle March for almost 35 years, became quite as well known for venality as his most notorious Scottish counterparts.

The Ulster Scots (Scotch Irish)

By the death of Elizabeth I of England, things had come to such a pitch along the Border that the English government considered re-fortifying and rebuilding Hadrian’s Wall, that artiicial entity which has divided Great Britain (Alba) for nearly two thousand years. When Elizabeth died, there was an especially violent outbreak of raiding known as “Ill Week”, resulting from the convenient belief that the laws of a kingdom were suspended between the death of a sovereign and the proclamation of the successor Upon his accession to the English throne, James VI of Scotland (who became James I of England) moved hard against the reivers, abolishing Border Law and the very term “Borders” in favour of “Middle Shires,” and dealing out stern “justice” to Reivers.

The border families can be referred to as clans, as the Scots themselves appear to have used both terms interchangeably until the 19th century. In an Act of the Scottish Parliament of 1597 there is the description of the “Chiftanis and chieffis of all clannis… duelland in the hielands or bordouris” – thus using the word clan and chief to describe both Highland and Lowland families. The act goes on to list the various Border clans. Later, Sir George MacKenzie of Rosehaugh, the Lord Advocate (Attorney General) writing in 1680 said “By the term ‘chief’ we call the representative of the family from the word chef or head and in the Irish (Gaelic) with us the chief of the family is called the head of the clan”. Thus, the words chief or head, and clan or family, are interchangeable. It is therefore possible to talk of the MacDonald family or the Maxwell clan. The idea that Highlanders should be listed as clans while the Lowlanders are listed as families originated as a 19th-century convention.

Other terms were also used to describe the Border families, such as the “Riding Surnames” and the “Graynes” thereof. This can be equated to the system of the Highland Clans and their septs. e.g. Clan Donald and Clan MacDonald of Sleat, can be compared with the Scotts of Buccleuch, from whom the present Earl of Ulster is descended, and the Scotts of Harden and elsewhere. Both Border Graynes and Highland septs however, had the essential feature of patriarchal leadership by the chief of the name, and had territories in which most of their kindred lived. Border families did practice customs similar to those of the Gaels, such as tutorship when an heir who was a minor succeeded to the chiefship, and giving bonds of manrent. Although feudalism existed, loyalty to kin was much more important and this is what distinguished the Borderers from other lowland Scots.

In 1587 the Parliament of Scotland passed a statute: “For the quieting and keping in obiedince of the disorderit subjectis inhabitantis of the borders hielands and Ilis.” Attached to the statute was a Roll of surnames from both the Borders and Highlands. The Borders portion listed 17 ‘clannis’ with a Chief and their associated Marches:

- Middle March

- Elliot, Armstrong, Nixon, Crosier

- West March

- Scott, Bates, Little, Thomson, Glendenning, Irvine, Bell, Carruthers, Graham, Johnstone, Jardine, Moffat and Latimer.

Of the Border Clans or Graynes listed on this roll, Elliott, Armstrong, Scott, Little, Irvine, Bell, Graham, Johnstone, Jardine and Moffat are registered with the Court of Lord Lyon in Edinburgh as Scottish Clans. Others such as Clan Blackadder were armigerous in the Middle Ages but later died out or lost their lands, and are unregistered.

The historic riding surnames, as recorded by George MacDonald Fraser in The Steel Bonnets (1989), are:

- East March

- Scotland: Hume, Trotter, Dixon, Bromfield, Craw, Cranston.

- England: Forster, Selby, Gray, Dunn.

- Middle March

- Scotland: Burn, Kerr, Young, Pringle, Davison, Gilchrist, Tait of East Teviotdale. Scott, Oliver, Turnbull (Trimble), Rutherford of West Teviotdale. Armstrong,Crosier, Elliot, Nixon, Douglas, Laidlaw, Turner, Henderson of Liddesdale.

- England: Anderson, Potts, Reed, Hall, Hedley of Redesdale. Charlton, Robson, Dodds, Milburn, Yarrow, Stapleton of Tynedale. Also Fenwick, Ogle, Heron, Witherington, Medford (later Mitford), Collingwood, Carnaby, Shaftoe, Ridley, Stokoe, Stamper, Wilkinson, Hunter, Thomson, Jamieson.

- West March

- Scotland: Bell, Irvine, Johnstone, Maxwell, Carlisle, Beattie, Little, Carruthers, Glendenning, Moffat.

- England: Graham, Hetherington, Musgrave, Storey, Lowther, Curwen, Salkeld, Dacre, Harden, Hodgson , Routledge, Tailor, Noble.

Relationships between the Border clans varied from uneasy alliance to open “deadly feud”. It took little to start a feud; a chance quarrel or misuse of office was sufficient. Feuds might continue for years until patched up in the face of invasion from the other kingdoms, or when the outbreak of other feuds caused alliances to shift. The border was easily destabilised if Graynes from opposite sides of the border were at feud. Feuds also provided ready excuse for particularly murderous raids or pursuits.

Long after they were gone, the reivers were romanticised by writers such as Sir Walter Scott( Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border), although he made mistakes; the term Moss-trooper, which he used, refers to one of the robbers that existed after the real Reivers had been put down. Nevertheless, Scott was a native of the borders, writing down histories which had been passed on in folk tradition or ballad. The stories of legendary border reivers like Kinmount Willie Armstrong were often retold in folk-song as Border ballads. There are also local legends, such as the “Dish of Spurs” which would be served to a border chieftain of the Charltons to remind him that the larder was empty and it was time to acquire more plunder. Scottish author Nigel Tranter revisited these themes in his historical and contemporary novels.

The names of the Rever families are still very much apparent amongst the inhabitants of the Scottish Borders, Northumberland, Cumbria, Ulster and Appalachia today. Reiving families (particularly those large enough to carry significant influence) have left the local population passionate about their territory on both sides of the Border. Newspapers have described the local cross-border rugby fixtures as ‘annual re-runs of the bloody “Battle of Otterburn”. Despite this there has been much cross-border migration since the Pacification of the Borders, and families that were once Scots now identify themselves as English and vice versa.

Hawick in Scotland holds an annual Reivers’ festival as do the Schomberg Society in Kilkeel, Northern Ireland (the two often co-operate). The summer festival in the Borders town of Duns is headed by the “Reiver” and “Reiver’s Lass”, a young man and young woman elected from the inhabitants of the town and surrounding area. The Ulster-Scots Agency’s first two leaflets from the ‘Scots Legacy’ series feature the story of the historic Ulster tartan and the origins of the kilt and the Border Reivers.

Borderers (particularly those banished by James VI of Scotland and I of England took part in the Seventeenth Century Settlement of Ulster becoming the people known as Ulster-Scots (Scotch-Irish in America). Reiver descendants can be found throughout Ulster with names such as Elliot, Armstrong, Beattie, Bell, Hume and Heron, Rutledge, and Turnbull (Trimble) amongst others.The Grahams were so detested by James that their very name was forbidden, so they cleverly reversed it and were known by the old Gaelic family name of Maharg.

Border surnames can also be found throughout the major areas of Scotch-Irish settlement in the United States, and particularly in the Appalachian region. The historian David Hackett Fischer (1989) has shown in detail how Border culture became rooted in parts of the United States. Author George MacDonald Fraser wryly observed or imagined Border traits and names among famous people in modern American history; Presidents Lyndon B. Johnston and Richard Nixon, among others. It is also noted that, in 1969, a descendant of the Borderers, Neil Armstrong, was the first person to set foot on the moon. In the following year, Mr. Armstrong visited the town of Langholm, home of his ancestors.

The artist Gordon Young created a public art work in Carlisle: Cursing Stone and Reiver Pavement, a nod to Gavin Dunbar, the Archbishop of Glasgow’s 1525 Monition of Cursing. Names of Reiver families, last of the Old British of the Middle Kingdoms, are set into the paving of a walkway which connects Tullie House Museum to Carlisle Castle under a main road, and part of the bishop’s curse is displayed on a 14-ton granite boulder. The time has come for us to lift that curse and proclaim our birthright to the Middle Kingdoms of our ancestors.

© Pretani Associates 2014