The Medieval Era

Patrick of Lecale

In 398 AD St Ninian had established the first Christian Church in what is now Scotland at Candida Casa (now Whithorn) in Galloway. Although little is known about this great Christian Saint of the Novantes, or the earliest history of his foundation, it is clear that in the fifth and sixth centuries Candida Casa was an important centre of evangelism to both Britain and the northern part of Ireland.

To Irish nationalists, however, the main credit for the introduction of Christianity to Ireland belongs to Patrick. Yet, despite Patrick’s pre-eminent place in the history of the Irish Church, we do not know just how much of his story is historically accurate. Ironically, the only first-hand accounts of Patrick come from two works which he reputedly wrote himself, the Confession and the Epistle to Coroticus. Further, the reference to his arrival in the Annals cannot be taken as necessarily factual either, as it is now believed that the Annals only became contemporary in the latter part of the sixth century, and fifth century entries were therefore ‘backdated’. While some republican nationalist historians still accept the earlier date of c. 460 for Patrick’s death, many eminent scholars of early Irish history tend to prefer the later date of c. 493. The question of Palladius and his mission from Rome leads to still more uncertainty, with some scholars even proposing the idea that there could have been ‘two’ Patricks. Francis Byrne suggested that “we may suspect that some of the seventh-century traditions originally referred to Palladius and have been transferred, whether deliberately or as a result of genuine confusion, to the figure of Patrick.”

This uncertainty must be borne in mind when we come to look at his story. Patrick was first brought to Ireland as a slave from Romanised Britain and sold to a Cruthinic chieftain called Milchu, who used him to tend flocks around Mount Slemish in County Antrim. After six years of servitude he managed to escape from Ireland, first going by boat to the Continent, then two years later returning to his parents in Britain. Despite his parents being anxious that he would now remain at home, Patrick had a vision of an angel who had come from Ireland with letters, in one of which was relayed the message: “We beg you, Holy youth, to come and walk amongst us once again.” To Patrick, the letters “completely broke my heart and I could read no more and woke up.”

Tradition tells that Patrick eventually made the journey back to Ireland, finally landing in County Down in the territory of Dichu (of the Ulaid) who became his first convert. Dichu’s barn (sabhall or Saul) near Downpatrick was the first of his churches. Among Patrick’s first converts were Bronagh, daughter of Milchu, and her son Mochaoi (Mahee). St Mochaoi was to found the great monastery of Nendrum on Mahee Island in Loch Cuan (Strangford Lough), and is associated with the saint in the legends which grew around Patrick’s name. These legends firmly place Down as the cradle of Christianity in Ireland. At Nendrum were first educated Colman, who was of the Cruthin, and Finnian, who was of the Ulaid. Colman founded in the early sixth century the famous See of Dromore in Iveagh, while Finnian, British Uinnian, following a visit to Candida Casa, founded the great school of Movilla (Newtownards) in Down. Finnian is also notable for bringing the first copy of the Scriptures to Ireland.

Patrick himself is said to have founded Armagh around 444, and the selection of a site so close to Emain Macha would strongly suggest that the Ulster capital was still the most powerful over-kingdom in Ireland at that time. As far as Nendrum is concerned, the picture of its development is much clearer in the 7th century, for no excavated finds have been found earlier than this.But from 639 onwards the Annals record the

deaths of Nendrum clergy, including bishops, abbots and a scribe..This would suggest an active, populous monastery, and an early litany says”nine times fifty monks laboured under the authority of Mochaoi of Noendruim”

On Wednesday 1st December, 2010, my wife and I attended an exhibition by the artist Martin Mooney at the Ava Gallery, Clandeboye, near Bangor, County Down at the invitation of Lindy Guinness, Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, my favourite descendant of the Cruthin people. I had the privilege of sitting beside Julie Mackie, who was there with her husband Paddy, of the famous Belfast Engineering Company. They live on Mahee Island and Julie told me of the tide mill on the Island, dated by dendrochronology to 619 AD, making it the oldest excavated tide mill in the world. I also met Martin Mooney, and was delighted to find out that he was the brother of two old friends, Marie and Anne, from my hospital days in Ards and Bangor Hospitals. Sadly Anne has since died but Marie was there. Martin and Marie are the cousins of the poet Ciaran Carson, Director of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry of Queen’s University, Belfast. Ciaran has written a beautiful translation of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, which he has inscribed to me,” for Ian-with all good wishes for whatever ford you have to cross”.

Comgall of the Cruthin

Most of the early monastic settlements in Ireland would have been quite basic arrangements — My late friend, Cardinal Tomás O Fiaich, aka Tom Fee, said we should picture them like modern holiday camps, with rows of wooden accommodation chalets grouped around a few central activity buildings. I visited him regularly at his official residence at Ara Coeli, Armagh during the Hunger Strikes when I helped him try to get them discontinued. We shared a deep love of Ulster and he put the Red Hand on his Cardinal’s crest. His favourite song was ” The Ould Orange Flute”, popularised by Richard Hayward. As a result of our friendship, Tomás wrote the foreword to the second edition of my book “Bangor, Light of the World”, now in its third edition,

Indeed, Bangor was by far the most important of the monastic settlements, founded in 555 on Ulidian territory by Comgall, perhaps the most famous of all the Cruthin. The name ‘Bangor’ comes from the medieval Beannchar, which may mean ‘pointed arrangement’, possibly referring to the pointed sticks in the wattled fence which would have surrounded the settlement or simply “Blessed Place” in the older Pictish or British tongue. There have been several derivations over the years. It was Bangor which would give the largest number of great names to Irish religious history, figures such as Columbanus, Gall, Moluag (Molua), Maelrubha, Dungal and Malachy.

Comgall, it is said, was born at Magheramorne, County Antrim, in 512 of the People of the Dalaradian Cruthin . Having shown great promise in his early years of a vocation to the Christian ministry, Comgall was educated under St Fintan at Clonenagh among the Loigis Cruthin, and is also said to have studied under Finnian at Clonard and Mobhi Clairenach at Glasnevin. Following his ordination as a deacon and priest, Comgall was imbued with a great missionary zeal and founded many cells or monasteries before finally establishing Bangor on the coast of County Down under the patronage of Cantigern, Queen of Dalaradia, whose life he had saved. To distinguish it from the other Bangors in the British Isles it became known as Bangor Mór, ‘Bangor the Great’.

The monastic settlement consisted of a large number of huts made of wattles situated around the church or oratory with its refectory, school, scriptorium and hospice. The whole establishment was surrounded by a vallum which consisted of a rampart and ditch. Life at Bangor was very severe. The food was sparse and even milk was considered an indulgence. Only one meal per day was allowed and that not until evening. Confession was held in public before the whole community and severe acts of penance were observed. There was silence at meal times and at other times conversation was restricted to the minimum. Comgall himself was extremely pious and austere and it is said that he arose in the middle of the night to recite psalms and say prayers while immersed in the nearby stream.

The strength of the community lay in its form of worship. The choral services were based on the antiphonal singing from Gaul, introduced into the West by Ambrose of Milan in the fourth century. Bangor became famous for this type of choral psalmody and it spread from there throughout Europe once more. The glory of Bangor was the celebration of a perfected and refined Laus Perennis and in singing this the community of Bangor entered into a covenant of mutual love and service in the Church of Jesus Christ. Because of the great number of students and monks attached to Bangor and its outlying daughter churches, it was possible to have a continuous chorus of the Divine Praise sung by large choirs which were divided into groups, each of which took regular duty and sang with a refinement not possible when St Martin was organising the raw recruits of Gaul.

One of the most important religious works produced at Bangor was the Bangor Antiphonary, now housed in the Ambrosian Library of Milan. The creed found in this work differs in wording from all others known and is in substance the original Creed of Nicaea. For this reason alone the Bangor Antiphonary may be considered one of the most precious relics of Western civilisation. ‘Correct’

belief, the now standard orthodoxy of the Christian Church, was established chiefly at the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (now Iznik in Turkey) in May 325 AD. The resultant Nicene Creed was an enlarged and explanatory version of the Apostles’ Creed in which the doctrines of Christ’s divinity and of the Holy Trinity were defined.

In the Antiphonary, there is a celebration of Bangor’s contribution to church history:

The Holy, valiant deeds Of sacred Fathers, Based on the matchless Church of Bangor; The noble deeds of abbots, Their number, times and names, Of never-ending lustre, Hear, brothers; great their deserts, Whom the Lord hath gathered To the mansions of his heavenly kingdom. Christ loved Comgall, Well, too, did he the Lord.

There is also a hymn to Comgall himself:

Let us remember the shining justice of our patron, St Comgall, glorious in deed, aided by the spirit of God and, by the holy and radiant light of the sublime Trinity, directing all things under his rule… Listen, everyone, to the deeds of this champion of God, who has been introduced to the secrets of the angels. From the first flowering of his youth his uprightness, strengthened by his faith, was nourished on the pages of the Law and was introduced to the joys of God. The virtues which he showed in his great life were abundantly in keeping with his faith… He set himself like a barrier of iron in front of the people to rout, to uproot and destroy all evil and to build and implant good for the benefit of all, like St Hieremia set on high…

Comgall, by all accounts, was a commanding personality. “Such was his reputation for piety and learning that multitudes flocked to his school from the most distant parts; it is well established that not less than 3,000 students and teachers were under his care at one time, including many of the most honourable in the land. The evangelistic zeal of Comgall was pre-eminent — down to the landing-place at the reef of rocks he led many a band of his disciples who were to embark on their frail coracles to spread the Gospel in European countries.”

At Bangor were compiled in all probability the original Chronicles of Ireland, and the beautiful poetry The Voyage of Bran. In this region too the old traditions of Ulster were preserved and these were moulded into the Gaelic masterpiece the Táin Bó Cuailgne (Cattle Raid of Cooley). The ancient ‘Ulster Chronicle’, from which it is believed the oldest entries in the Annals of Ulster were derived, has been attributed to Sinlan Moccu Min, who is described in the lists of abbots in the Bangor Antiphonary as the “famed teacher of the world” (famosus mundi magister).

Proinsias Mac Cana has summed up the rich cultural legacy of this region of Ulster: “In Ireland the seventh century was marked by two closely related developments: the rapid extension of the use of writing in the Irish language and an extraordinary quickening of intellectual and artistic activity which was to continue far beyond the limit of the century. The immediate sources of this artistic renewal were the scriptoria of certain of the more progressive monasteries and its direct agents,

those monastic literati whom the Irish metrical tracts refer to by the significant title of nualitride, ‘new men of letters’.

While there is no reason to suppose that these individuals were confined to any one part of the country, nevertheless the evidence strongly suggests that it was only in the east, or more precisely the south-east, of Ulster that their activities assumed something of the impetus and cohesiveness of a cultural movement. Here conservation and creativity went hand in hand: the relatively new skill of writing in the vernacular began to be vigorously exploited not only for the direct recording of secular oral tradition– heroic, mythological and the more strictly didactic — but also at the same time as a vehicle for the imaginative re-creation of certain segments of that tradition, so that one may with due reservations speak of this region of south-east Ulster as the cradle of written Irish literature… Bangor seems to have been the intellectual centre whence the cultural dynamic of the east Ulster region emanated.”

Columba or Columb-Cille of Iona

One of the great religious figures of Ireland was Columba (Columb-Cille) claimed to have been a prince of the “Northern Uí Néill”; his father, it is said, being the great-grandson of Niall of the Nine Hostages. It is more probable however that Columba’s clan, the Cenel Conaill, were actually Cruthin or Pretani (Ancient British) and not “Uí Néill” at all. Columba studied under St Finnian, the British Uinnian, at Movilla, where he was ordained deacon. According to the Annals of Ulster, he founded Derry in 545, although it is more probable that his relative Fiachra mac Ciaráin, who died in 620, was the actual founder, so that the term Derry Columb-Cille is a nonsense. It should actually be Derry Calgach, the Oakwood of the British Prince Calgacus, a chieftain of the Caledonian Confederacy. Columba became a close friend of Comgall’s, even though the political rivalries between their respective kinsmen must at times have sorely tested their shared Christianity.

Columba’s biographer, Adomnán (often translated as Adamson in English), the ninth abbot of Iona from 679-704, describes such an incident which highlights the communal conflicts of the period:

At another time [Columba] and the abbot Comgall sit down not far from the fortress [of Cethirn], on a bright summer’s day. Then water is brought to the Saints in a brazen vessel from a spring hard by, for them to wash their hands. Which when St Columba had received, he thus speaks to the abbot Comgall, who is sitting beside him: ‘The day will come, O Comgall, when that spring, from which has come the water now brought to us, will not be fit for any human purposes.’ ‘By what cause,’ says Comgall, ‘will its spring water be corrupted?’ Then says St Columba, ‘Because it will be filled with human blood, for my family friends and thy relations according to the flesh, that is, the Uí Néill and the Cruthin people, will wage war, fighting in this fortress of Cethirn close by. Whence in the above-named spring some poor fellow of my kindred will be slain, and the basin of the same spring will be filled with the blood of him that is slain with the rest.’ Which true prophecy of his was fulfilled in its season after many years.

The saint’s legend would have us believe that it was these political and ethnic distractions which finally persuaded Columba to leave Ireland and set up a new community out of sight of its shores. Yet although Columba had not stood aloof from political intrigue, or even inciting warfare, such involvement would not have been exceptional for the clergy at that time, some of whom carried weapons to the synods.

As J. T. Fowler wrote: “It is no marvel then if Columba, a leading spirit in the great clan of the northern Uí Néill, incited his kinsmen to fight about matters which would be felt most keenly as closely touching their tribal honour. But at the same time, such a man as he was may very well, upon calm reflection, have considered that his enthusiasm and energies would be more worthily bestowed on missionary work than in maintaining the dignity of his clan.”

Whatever the reasons for his departure, the history of the Church was to be so much the richer, for the community he founded, on the small island of Iona, close to the coast of Argyll, was destined to be the cultural apotheosis of Scotland, and the place where some scholars believe the magnificent Book of Kells was executed.

Our Ullans group of long time friends, of every opinion under the sun, meet at Bell’s Coffee Shop at the Knock intersection on the Upper Newtownards Road in Belfast every week. Knock, of course, is the English for Cnoc, a hill, this being Cnoc Columb-Cille , the Hill of the Church of Columba, so he is still with us in Saint Columba’s Parish Church there. And Adomnán first notes Conlig in history when Columba visits a rich peasant called Foirtgirn at mons Cainle, the hill of Conlig.

The northern Irish monastic settlements, whether their influence emanated from Bangor or Iona, were not only to be directly responsible for the spread of Christianity to Scotland and northern England, but were to carry their missionary zeal to the very heart of Europe itself. Of all the numerous personalities who sought “to renounce home and family like Abraham and seek a secluded spot where the ties of the world would not interfere with their pursuit of sanctity” none stands out more prominently among these peregrini than Columbanus. To be continued

Columbanus of Europe

Columbanus, it has been said, was born of the old Leinster Pretani, about the year 543. His biography was written on the continent in the last monastery he himself founded, and while it contains much detail of his career in Europe, it is sparing with facts about his youth in Ireland, and in it, as with all such documents, fact and fiction are no doubt well enmeshed.The legend has it that when still a young man he decided to enter the religious life, and fearful that the ties of matrimony might prevent this — for he was reputedly a handsome youth who had already attracted female admirers — he decided to leave home for ever and go north to Ulster. When his mother tried to dissuade him from departing by throwing herself down across the threshold, Columbanus strode over her prostrate body. It is unlikely that he ever saw her again.

He travelled first to the island of Cleenish on Lough Erne where he received his early education under the celebrated scholar Sinell. His strength of purpose was that required by Comgall of his monks and so it was natural that Columbanus should come to the Pretanic foundation at Bangor where he remained for many years as a disciple and friend of Comgall. In 589 Columbanus set off from Bangor on what was to become one of the great missionary journeys of history. With him he had twelve companions, including his devoted friend, Gall. The European Continent on which Columbanus and his party set foot had experienced radical change. The Roman Empire and its widespread organisational network had disintegrated under the impact of the barbarian invasions, and now, instead of Roman proconsuls, barbarian kings and dukes established their rule over Europe.

Under the first surge of these ‘barbarians’, not only had the Roman system of government disappeared, but order and learning had virtually collapsed and the practice of Christianity had been almost completely extinguished. Ireland, however, had not only been unaffected by these barbarian invasions, but had only been indirectly touched by Roman ‘civilisation’, which, in the rest of Europe had brought, alongside its beneficial aspects, an equally ruthless ‘barbarianism’ in its suppression of older European cultures. So not only had the Church survived intact in Ireland, but its traditions of learning had continued unimpaired.

In 590 the small group of missionaries arrived in the Merovingian kingdom of Burgundy, where Gunthram, king of Burgundy and Austrasia, received them warmly and established them at a place called Annegray which was the site of a derelict Roman castle. Here the monks repaired the ruined Temple of Diana and made it into their first church, rededicating it to St Martin of Tours. The king offered them every appreciation in terms of food and money but they declined, preferring to keep to the monastic ideals to which their lives were committed. Columbanus himself was wont to walk deep into the Burgundian forest, heedless of either starvation or danger, taking with him only the Bible he had transcribed in his beloved Bangor.

The king’s ready support need not surprise us. Although the initial barbarian population movements had destroyed the existing Roman system, the barbarian chiefs still held the empire in awe. Christianity not only carried with it the great prestige of Roman civilisation, but consisted of a more coherent body of doctrine than the vast assortment of pagan gods, and therefore offered more advantages, both personal and political, to the newly emerging ruling elites. This soon encouraged a gradual revival of the dormant church.

As the number of monks in the monastery at Annegray increased daily, it became necessary for the community to seek a more suitable site. King Gunthram had died in

593 and young Childebert II now ruled over Burgundy and Austrasia. His permission was given to build a second monastery eight miles west of Annegray, beside the River Breuchin, among the ruins of the former Roman fort at Luxovium, which had been completely destroyed by Attila and his Huns in 451.

Here at the foot of the Vosges mountains, close by a healing stream, there arose the great Community of Luxeuil. Although Jonas claimed that the site had been completely deserted and overgrown, there was already a Christian site there, which exactly suited Columbanus, for he loved manual labour as much as he loved solitude. So great did the community here become that the noble youths of the Franks asked to be admitted to its brotherhood, and eventually it was necessary to establish a third foundation at Fontaine, three miles north of Luxeuil. (In fact, Luxeuil was to influence directly or indirectly nearly one hundred other religious foundations before the year 700.)

The community of Columbanus was now growing so large it became necessary to draw up written rules for the guidance of the monks. These rules were no doubt modelled on the Good Rule of Bangor written by Comgall. These rules covered everything from timetables for the recitation of psalms to instructions for obedience, fasting, and daily chanting. Some of the régime must seem harsh and authoritarian to us today, particularly the punishments to be meted out for infringements of the rules, these punishments usually being inflicted with a leather strap on the palm of the hand:

“The monk who does not prostrate himself to ask a prayer when leaving the house, and after receiving a blessing does not bless himself, and go to the cross — it is prescribed to correct him with twelve blows. The monk who will eat without a blessing — with twelve blows. The monk who through coughing goes wrong in the chant at the beginning of a psalm — it is laid down to correct him with six blows. The one who smiles at the synaxis, that is, at the office of prayers — with six blows; if he bursts out laughing aloud — with a grave penance unless it happens excusably. The one who receives the blessed bread with unclean hands — with twelve blows.”

Some of the rules showed a more insightful approach: “The talkative is to be punished with silence, the restless with the practice of gentleness, the gluttonous with fasting, the sleepy with watching, the proud with imprisonment, the deserter with expulsion.”

While such rules of discipline show that Columbanus was strict in his approach to organising the daily life of his monasteries — and he was just as strict with himself — he was also well known for his warmth and understanding. His thoughtfulness about human relationships is shown in this letter he wrote to a young disciple:

“Be helpful when you are at the bottom of the ladder and be the lowest when you are in authority. Be simple in faith but well trained in manners; demanding in your own affairs but unconcerned in those of others. Be guileless in friendship, astute in the face of deceit, tough in time of ease, tender in hard times. Disagree where necessary, but be in agreement about truth. Be slow to anger, quick to learn, also slow to speak, as St James says, equally quick to listen. Be up and doing to make progress, slack to take revenge, careful in word, eager in work. Be friendly with men of honour, stiff with rascals, gentle to the weak, firm to the stubborn, steadfast to the proud, humble to

the lowly. Be ever sober, ever chaste, ever modest. Be patient as far as compatible with zeal, never greedy, always generous, if not in money, then in spirit.”

Luxeuil quickly became the most celebrated monastery in Christendom after Bangor itself. Both sacred and classical studies were of the utmost importance. The art of music was prominent as in Bangor and was taught at a level at that time unknown in Europe. H. Zimmer has written: “They were the instructors in every branch of science and learning of the time, possessors and bearers of a higher culture than was at that time to be found anywhere on the Continent, and can surely claim to have been the pioneers — to have laid the cornerstone of western culture on the Continent.”

The Easter Controversy

Columbanus’ penitential discipline and his independence of action infringed upon the powers of the local Frankish bishops, and he probably had few friends among them. When he insisted on celebrating Easter according to the British calculations he was accused of unorthodoxy by the Roman bishops. In the British Isles Easter was calculated on entirely different principles from the rest of Christendom, from a table known by an irregularly formed Latin word as the Latercus and attributed to Sulpicius Severus in the mid-4th century. A careful choice of initial epact ensured that , like the Alexandrian computus, and unlike either Augustalis or the Supputatio Romana, the Latercus gave a single Easter date for every year.

Columbanus insisted on using the Latercus and relationships between him and the local bishops deteriorated still further. In a letter to Pope Gregory the Great which veiled strong-mindedness in humility, he defended his practice,declaring that the learned among his countrymen had rejected the orthodox Victorius’ tables as more worthy of pity than of scorn, that Easter should be celebrated when the moon did not rise later than midnight thus celebrating the triumph of light over darkness; and that celebration on the same day as the Jews was no problem because Pascha belonged not to them but to the Lord (Exod.12:11).

Matters finally came to a head when he incurred the displeasure of the secular rulers also. Theuderich, the new young king of Burgundy, although married, installed concubines in the royal household, and soon had four illegitimate children. When the king’s grandmother, Brunhilde, instructed Columbanus to confirm her grandson’s illegitimate children, he refused, and from then on she was to prove his bitter enemy. Brunhilde may have inspired the story of Brynhildr, the shieldmaiden and valkyrie in the mythology of the Vikings, when she appears in the Völsunga saga and the Eddic poems. As Brünnhilde she also appears in the Medieval German masterpiece, the Nibelungenlied, a heroic epic of equal stature to Homer’s Iliad, and thus in Wagner’s magnificent Der Ring der Nibelungen, though some would deprecate Wagner’s alterations to the story. Attila the Hun also appears in the epic as Etzel, husband of Kriemhild.

This confrontation may have been embellished somewhat by Columbanus’ biographer, for, as Ian Wood points out, Columbanus “was not the first to criticise Merovingian concubinage; it would, in fact, be curious if an Irishman, coming from an island where royal concubinage was even more entrenched than in Francia, had been the first to condemn the practice.”

Whatever the actual details, in 610 Brunhilde succeeded in having Columbanus expelled from his beloved monastery, never to see it again. He and his party of Irish monks then embarked on a 600 mile journey westwards to the coast. Once there, they boarded a vessel which was to take them back to Ireland. However, a great storm arose and drove the boat back to the shore, where for the next three days it then became becalmed. The captain, believing all these events were a sign from God that he was not to co-operate in the expulsion of the Irish monks, set them back onto the shore again.

Another great journey now lay ahead of Columbanus and his party, made longer by the need to take a wide detour whereby they would avoid contact with their

Burgundian adversaries. Finally, after much hardship they established their new headquarters close to Lake Constance at Bregenz (which lies in present-day Austria close to its borders with Switzerland and Germany). Here they built a small cloistered monastery, laid out a garden and planted fruit trees. But nature proved more yielding to their efforts than the local people, many of whom were deeply resentful of these intruders who had the effrontery to smash their pagan images and throw them into the lake.

When some of the monks were murdered, Columbanus realised that once again he must uproot himself and his community and seek elsewhere for a sanctuary. However, not all his monks were prepared to embark on further travel into the unknown, including Gall, who throughout these years of hardship had probably been Columbanus’ closest companion. When Gall broke the news to his aging friend, their parting must have been one of the most sorrowful occasions in both their lives.

Although by now more than seventy years of age, Columbanus crossed the snow-covered Alps through the St Gothard’s pass and made his way to the court of the Lombard king, who granted him a suitable place, at Bobbio, where he could found a new monastery. Columbanus was to die a year later but Bobbio was to grow in stature, attracting some of the finest scholars of the time and containing a splendid library of over 700 books, and became the most important monastic centre in Northern Italy. Several dozen manuscripts, some lavishly illuminated, have survived from the first three centuries of Bobbio’s existence. The largest extant body of Old Irish glosses passed through the monastery before ending up in Milan.

Before he died Columbanus sent a messenger to seek out his old friend Gall, to let him know that the bitterness of their parting had been finally set aside. The great emperor Charlemagne was to build one of his most famous foundations — the Monastery of St Gall — near the spot where Columbanus’ old travelling companion had lived the austere life of a hermit. A modern monastery now stands there today, of which it has been written: “The monastery… has in its library beautiful Irish manuscripts made by some of these travelling scholars.

The library has also preserved a fine plan of Charlemagne’s monastery with its sties and stables, its sheepfolds and fowl houses, threshing floors and market gardens… As well as this farm neatly laid out in a great rectangle around the central church, the monastery of St Gall had a hostel and a kitchen for its guests, schools and accommodation for the abbot and his monks, a doctor’s clinic, an infirmary and a cemetery. Such settlements formed the high culture of Europe in the reign of Charlemagne.”

G.S.M. Walker wrote of Columbanus: “A character so complex and so contrary, humble and haughty, harsh and tender, pedantic and impetuous by turns, had as its guiding and unifying pattern the ambition of sainthood. All his activities were subordinate to that one end and with the self-sacrifice that can seem so close to self-assertion he worked out his sole salvation by the wondrous pathway that he knew. He was a missionary through circumstance, a monk by vocation, a contemplative, too frequently driven to action by the world, a pilgrim on the road to Paradise.” Pope Pius XI has said, “The more light that is shed by scholars in the period known as the Middle Ages the clearer it becomes that it was thanks to the initiative and labours of Columbanus

that the rebirth of Christian virtue and civilisation over a great part of Gaul, Germany and Italy took place.”

The French poet Leon Cathlin concurs in saying, “He is, with Charlemagne, the greatest figure of our Early Middle Ages,” and Daniel-Rops of the French Academy has also said that he was “a sort of prophet of Israel, brought back to life in the sixth century, as blunt in his speech as Isaias or Jeremias… For almost fifty years souls were stirred by the influence of St Columbanus. His passing through the country started a real contagion of holiness.” More recently, Robert Schuman, the French Foreign Minister who was a driving force behind the establishment of the European Economic Community, said: “Columbanus is the patron saint of those who seek to construct a united Europe.”

In 2012 we celebrated the 1400th anniversary of Bobbio’s foundation.. Having started with the Farset Steps of Columbanus Project in the mid ’80’s with the help of Tomas Cardinal O’Fiaich and Archbishop Robin, now Lord, Eames the Ullans Academy continued with Feast of Columbanus events with Dr Ian Paisley (Lord Bannside), Baroness Eileen Paisley, and President Mary McAleese and Michael D Higgins. Through Pretani Associates, on 22nd November, 2015, they commemorated the 1400th anniversary of Columbanus’s death in 615 by honouring him as the Patron Saint of Bikers. This event was held under the auspices of Eddie Irvine at his Sports Centre in Bangor. Eddie himself attended with Biker legends Jeremy Mc Williams and Alistair Seeley and the Bikers of Dalaradia. The President of Ireland, Michael D Higgins sent a message of support.

It isn’t just for their religious impact that the Irish monks are renowned, but for the manner in which they inscribed and illuminated their magnificent manuscripts. “Drawing upon the traditional art of their pagan past, Irish monks decorated their great manuscript books and the accoutrements of their churches with designs that are a breathtaking reminder of the art of their forebears… Margins overflow with patterns of swirling, interlocking lines, and entire pages are given over to scriptural pictures that are a kaleidoscope of colour and restless patterns. Perhaps the most famous of these Bible pages are the dazzling ‘carpet pages’, covered in their entirety with patterns that rival the delicacy of the finest metalwork and the brilliance of enamel or precious stones.” Some of these manuscripts, notably the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, and the Lindisfarne Gospels, are considered to be among the world’s greatest art treasures.

The Battle of Moira

While Irish missionaries were spreading the message of Christianity throughout Europe the Irish at home had not allowed themselves to be deflected from their proclivity for martial conflict. Around 450, after Emain Macha had been destroyed, or abandoned, as a result of the initial “Uí Néill” advance, the Ulstermen had retreated east, and in this reduced kingdom of Ulster they attempted to stabilise their power, with the erection of the “Dane’s Cast” earthworks as a visible reminder to their adversaries that they were in no respects a spent force. The Cruthin confronted the “Uí Néill” in 563 at the battle of Móin Dairi Lothair (Moneymore). However, seven kings of the Cruthin were killed in this battle, and the way was open for the “Northern Uí Néill” victors to expand into what is now County Londonderry.

In the Annals of Ulster the compiler, when giving mention of this battle, also records it in verse:

Sharp weapons stretch, men stretch, In the great bog of Daire-lothair — The cause of a contention for right — Seven Cruthin Kings, including Aedh Brec (Freckled Hugh). The battle of all the Cruthin is fought, [And] they burn Eilne (Ballymoney). The battle of Gabhair-Lifè is fought, And the battle of Cul-dreimne.

Two years later the Cruthin over-king of Ulster, Aed Dub mac Suibni (Dark Hugh Mac Sweeney), slew the “Northern Uí Néill” king, Diarmait mac Cerbaill. A battle is also recorded between the Cruthin and the Uí Néill near Coleraine in 579. However, it was to be at the great battle of Moira in 637 that the Ulstermen were to make their most determined effort to call a halt to “Uí Néill” expansion.

Congal Cláen, possibly the greatest of all Cruthin kings, became over-king of Ulster in 627. In 628 he slew Suibne Menn, the “Uí Néill” “high-king”, but was in turn defeated by the new “high-king” at Dún Ceithirn in Derry two years later (the battle which Columba’s biographer tells us the saint had prophesied to Comgall, the Cruthin abbot of Bangor).

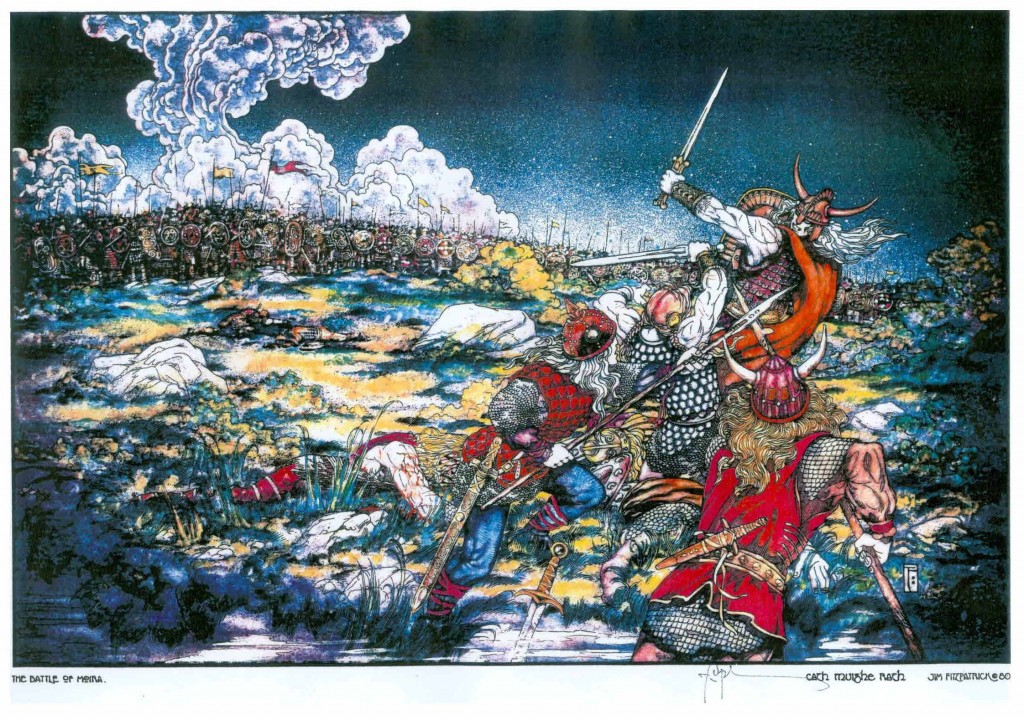

By 637, however, Congal had managed to gather around him a powerful army, which included not only his Ulstermen, but, according to Colgan, contingents of Picts (Scotland), Anglo-Saxons (English) and Britons (Welsh). The battle, as depicted in later Bardic romances, seems to have been a ferocious affair, and as well as the land confrontation it included a naval engagement.

The Annals of Tigernach record the battle as follows: AD 637. The Battle of Magh Rath, gained by Domnall, son of Aed, and by the sons of Aed Sláine — but Domnall at this time ruled Temoria — in which fell Congal Caech king of Ulaidh and Faelan, with many nobles; and in which fell Suibne, son of Colmán Cuar.

In 1872, Sir Samuel Ferguson — born in 1810 and the finest poet of 19th century Ireland — published his masterpiece Congal, based on the Bardic romance ‘Cath Muighe Rath’ (Battle of Moyra). Ferguson’s poem is in the grand epic style of the old Irish bards, and it is easy to imagine that this is how they too would have described the mortally wounded king, as he staggered from the battlefield, half-conscious and little knowing what was transpiring around him:

But, rapt in darkness and in swoon of anguish and despair, As in a whirlwind, Congal Cláen seemed borne thro’ upper air; And, conscious only of the grief surviving at his heart, Now deemed himself already dead, and that his deathless part Journeyed to judgement; but before what God’s or demon’s seat Dared not conjecture; though, at times, from tramp of giant feet And heavy flappings heard in air, around and underneath, He darkly surmised who might be the messenger of death Who bore him doomward: but anon, laid softly on the ground, His mortal body with him still, and still alive he found. Loathing the light of day he lay; nor knew nor reck’d he where; For present anguish left his mind no room for other care; All his great heart to bursting filled with rage, remorse and shame, To think what labour come to nought, what hopes of power and fame Turned in a moment to contempt; what hatred and disgrace Fixed thenceforth irremovably on all his name and race… Then Congal raised his drooping head, and saw with bloodshot eyes His native vale before him spread; saw grassy Collin rise High o’er the homely Antrim hills. He groaned with rage and shame. “And have I fled the field,” he cried; “and shall my hapless name “Become this byword of reproach? Rise; bear me back again, “And lay me where I yet may lie among the valiant slain.”

In an article reviewing Reeves’ Ecclesiastical Antiquities, Ferguson, who typified the Ulster intellectual of his day — intensely proud of his ‘Gaelic’ heritage, but without the rancour of the xenophobe — wrote:

“We are here upon the borders of the heroic field of Moyra, the scene of the greatest battle, whether we regard the numbers engaged, the duration of combat, or the stake at issue, ever fought within the bounds of Ireland. For beyond question, if Congal Cláen and his Gentile allies had been victorious in that battle, the re-establishment of old bardic paganism would have ensued. There appears reason to believe that the fight lasted a week; and on the seventh day Congal himself is said to have been slain by an idiot youth, whom he passed by in battle, in scorn of his imbecility. All local memory of the event is now gone, save that one or two localities preserve names connected with it. Thus, beside the Rath of Moyra, on the east, is the hill Cairn-Albanach, the burial-place of the Scottish princes, Congal’s uncles; and a pillar-stone, with a rude cross, and some circles engraved on it, formerly marked the site of their resting-place. On the other hand, the townland of Aughnafoskar probably preserves the name of Knockanchoscar, from which Congal’s druid surveyed the royal army, drawn up in the plain below, on the first morning of the battle. Ath Ornav, the ford crossed by one of the armies, is probably modernised in Thorny-ford, on the river, at some miles distance. On the ascent to Trummery, in the direction of the woods of Killultagh, to which, we are told, the routed army fled, great quantities of bones of men and horses were turned up in excavating the line of the Ulster Railway which passes close below the old church.”

Congal Claen – The Battle of Belfast

The Annals of the Four Masters record that in 665 AD, the Battle of Farset (Belfast) took place between the County Down Dal Fiatach, self styled Ulaid, and the Pretani or Cruthin where Cathasach, son of Laircine, was slain. This was an attempt by the Dal Fiatach to encroach on the Cruthin territory of Trian Congail. the “third of Congal”, which encompassed territory on both sides of the Lagan, corresponding more or less to Upper and Lower Clandeboye, including modern Belfast. Cathasach was Congal’s grandson. The battle was the first mention of Belfast in Irish history.

The story of Congal Cláen has a bearing on another aspect of Irish history — the question of the ‘high-kingship’ of Ireland. Late seventh century writers claimed that the “Uí Néill” had held the high-kingship of Ireland for many centuries. Yet in the study of that early period of Irish history little evidence is found of a centralised monarchy. Indeed, at any given time between the fifth and twelfth centuries there were probably no less than 150 tribal kings throughout the island.

Francis Byrne has commented: “In later ages this multiplication of monarchies caused some embarrassment to patriotic Irishmen who had been brought up to believe in the glories of the high-kingship centred in Tara… The title ard-rí… has no precise significance, and does not necessarily imply sovereignty of Ireland… It is now evident that Niall and his descendants for many centuries can in no real sense be described as high-kings of Ireland. The claims made for them… must be discounted as partisan: few other contemporary documents show special deference being afforded to the “Uí Néill” outside their own sphere of influence, and the laws do not even envisage the office of high-king of Ireland.”Ironically, the only reference to Tara throughout all the Old Irish legal tracts concerns, not a member of the Uí Néill dynasty, but Congal Cláen of the Cruthin. Bechbretha, an eighth century law tract, details, among many other matters, how blame should be apportioned for bee stings, stating the following:

“If it be an eye which it has blinded, it is then that it (the injury) requires the casting of lots on all the hives; whichever of the hives it falls upon is forfeit for its (the bee’s) offence. For this is the first judgement which was passed with regard to the offences of bees on Congal the One-eyed, whom bees blinded in one eye. And he was king of Tara until [this] put him from his kingship.” The matter of Congal losing the high-kingship refers to the prohibition on anyone with a blemish holding this position.

As Francis Byrne comments: “This is the only reference in the law-tracts to Tara (and) it runs directly contrary to the accepted doctrine that it was a monopoly of the Uí Néill… When we remember that the Ulaid and Cruthin were still powerful in County Londonderry and possibly still ruled directly in Louth as far as the Boyne in the early seventh century; that they cherished memories of their former dominance over all the North; that they considered the Uí Néill recent upstarts… it is not difficult to imagine that they could with some justice lay claim to Tara.”

However, whatever arguments the Ulstermen could have produced to support such a claim were immaterial after 637. The Battle of Moira effectively put an end to any hopes they might have harboured that they could undo the “Uí Néill” gains. For although the Ulstermen were still to retain

their independence in the east of the province for another 500 years, the Uí Néill were now firmly entrenched as the dominant power in the North.

As well as their continued victories against the Ulstermen — the Ulaid suffered a severe defeat at Fochairt near Dundalk in 735 — the “Uí Néill” also continued to encroach upon the territory held by the Airgialla in the centre of the ancient province. It was probably their alarm at this continuing advance which explains why the Ulstermen fought alongside the Airgialla at the battle of Leth Cam (near Armagh) in 827, in which the “Uí Néill” emerged victorious yet again, with many kings of the Airgialla being slain. Whatever autonomy had been held by the Airgialla was now destroyed and their kings became mere vassals of the “Uí Néill”.

Despite these reverses, the Ulstermen were still determined to resist, and in 1004 another great battle was fought at Cráeb Tulcha (Crew Hill Glenavy), in which the Cruthin king, the Ulaid king, and many princes of Ulster, were killed — indeed, complete disaster was possibly only averted because the victorious “Uí Néill” king was also one of the fatalities. The Annals of Ulster thus record the event:

The battle of Craebh-telcha, between the Ulidians and Cinel-Eoghain, where the Ulidians were defeated, and Eochaid, son of Ardgar, King of Ulidia, and Dubhtuinne his brother, and his two sons, viz., Cuduiligh and Domnall, were slain, and a havoc was made of the army besides, between good and bad, viz., Gairbhith, King of Uí-Echach (Iveagh), and Gilla Patraic son of Tomaltach, and Cumuscach son of Flathroe, and Dubhslanga son of Aedh, and Cathalan son of Etroch, and Conene son of Muirchertach, and the elect of the Ulidians besides. And the fighting extended to Dun-Echdach, and to Druim-bó. There also fell there Aedh, son of Domnall Ua Neill, King of Ailech, (and others, in the 29th year of his age, and the 10th year of [his] reign). But the Cinel-Eoghain say that he was killed by themselves. Donnchad Ua Loingsigh, King of Dal nAraidi (Dalaradia), was treacherously killed by the Cinel-Eoghain.

No doubt many of the original peoples of Ulster remained in the territories now dominated by the “Uí Néill” overlords, but their former dynastic leaders from within the Cruthin and the Ulaid were confined to that area which today comprises counties Antrim, Down and north Louth. Yet, so long as these Ulster kingships endured, no matter how reduced might be the realm over which their suzerainty could lay claim, the “Uí Néill” could never call themselves kings of Ulster. Cruthin and Ulaid kings shared in the high-kingship of this reduced Ulster, though at times the strains within the alliance would lead to open warfare (it was a battle between the Cruthin and Ulaid, recorded in the Annals of Ulster as having been fought at the ‘Fearsat’ in 667 which gave Belfast its first mention in history). The independent territories became known by the names of the ruling dynasties, prefixed by the term in Gaelic for ‘a portion’ —‘Dál’ (Gaelic by now being the dominant language throughout Ireland).

Within the Ulaid the dominant dynasty were the Dál Fiatach, who ruled over the maritime areas between Dundrum Bay and Belfast Lough, with the centre of their power established at Downpatrick. Another grouping, the Dál Riata, held territory in the north-eastern part of Antrim, called Dalriada.

It was, however, the Cruthin who formed the bulk of the population, and their territories comprised the remainder of the area of Antrim and Down, although for some time after the initial “Uí Néill” advances they had managed to retain their hold on territory northwards to Lough Foyle and southwards to Dundalk Bay. There is evidence of the existence of from seven to nine petty kingdoms of the Cruthin around the sixth century. Their main dynasty was the Dál nAraidi, and the area they

ruled over became known in English as Dalaradia (not to be confused with Dalriada in the north-east). The kings of Dál nAraidi resided at Ráth Mor, where a ringfort remains to this day, just east of Antrim town. Another group within the Cruthin who also provided over-kings of Ulster were the Uí Echach Cobo, who inhabited the present baronies of Upper and Lower Iveagh and Kinelarty.

The Gaelic Occupation

When the Gaelic dynasties became indisputably into their ascendancy, their learned men sought to provide them with a lineage that would glorify their remarkable achievements. Furthermore, the Gaelic invaders had not only imposed their military control over much of Ireland, but, perhaps due to their great influence, prestige and positions of ‘political’ power, their language had now become widely accepted among the Irish population, certainly among the learned classes and within the developing Church. No doubt the mass of the population for a long time retained much of their own language or languages — references in ancient texts indicate this was so — but these languages must inevitably have gone into decline, although with many British loan-words being incorporated into the new ‘Irish’ language, which, however, continues to be known as Gaeilge or Gaelic. spoken in Gaeltacht areas. Gaelic nationalism remains the root of the problem in Northern Ireland.

The clergy, who had been to the forefront of the development of writing, had originally used Latin, but eventually it was they who were to give the lead to the creative flowering of vernacular Irish literature. The clergy did not limit their efforts just to religious topics, but to the transformation of the wealth of oral tradition into a remarkably rich body of secular literature. And, of course, to the construction of ‘genealogies’ which would establish suitable pedigrees for the ruling classes.

That the dominant classes desired to see themselves thus promoted should hardly surprise us — most ruling establishments throughout history have always sought to see their credentials well established, not just for the pragmatic political needs of the moment but often with an eye to posterity. And so the Gaelic genealogists set to their task with an energy and inventiveness which even today provokes admiration from scholars.

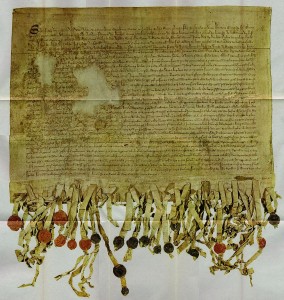

One of the main works produced as a result of this intensive effort was the Lebor Gabála, the ‘Book of Invasions’, which sought to enumerate all the successive invasions of Ireland and all the peoples who partook in those invasions. Leaving aside its genealogical purpose, the account stands by itself as a fascinating collection of legends, within which stalk mysterious peoples and their powerful heroes, constantly fighting gigantic battles — and which can still today provide a rich source of inspiration, as is witnessed by the beautifully imaginative illustrations of Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick.

Within this account the ancestors of the Gaels are said to have sprung from two sons of Míl, a warrior who had come to Ireland from Spain. In the earliest version (eighth century) only a limited number of ethnic groupings are awarded this important pedigree, while all others are relegated to an inferior status. Then, in a later, ‘revised edition’ of Lebor Gabála, Míl seems to have posthumously increased his sons, for a third, Ir, is now present. As T.F. O’Rahilly commented: “The invention of Ir was probably due in the first instance to the genealogists, who were favourably disposed towards the Cruthin and determined to provide them with a highly respectable Goidelic [Gaelic] pedigree.”

This process continued, with other important Irish dynasties being incorporated into the Milesian family tree, the number of Míl’s sons eventually increasing to eight. However, as Francis Byrne pointed out, “the mythological material is so rich and varied that not even the most assiduous monkish synchroniser nor the most diplomatic fabricator of pedigrees could bring complete order into this chaos. The resultant inconsistencies and anachronisms give us valuable clues.”

T. F. O’Rahilly, in his monumental work Early Irish History and Mythology, tried to reassemble the jigsaw of early Irish origins, although his conclusions as to who the various peoples in Lebor Gabála might have been are questioned today. Nevertheless, O’Rahilly neatly summed up the process by which the Gaelic genealogists undertook their task:

“In the early Christian centuries the ethnic origins of the different sections of the Irish population were vividly remembered, so much so that one of the chief aims of the early Irish historians and genealogists, was to efface these distinctions from the popular memory. This they did by inventing for the Irish people generally (apart from the lower classes, who did not count) a common ancestor in the fictitious Míl of Spain…”

“The ‘learned’ authors of that elaborate fiction, the invasion of the Sons of Míl, and the genealogy-makers who collaborated with them, were animated by the desire to invest the Goidelic occupation of Ireland with an antiquity to which it was entitled neither in fact nor in tradition; for only in this way would it be feasible to provide a Goidelic descent for tribes of non-Goidelic origin, and to unify the divergent ethnic elements in the country by tracing them back to a common ancestor… [By] obliterating the memory of the different ethnic origins of the people… the tribes of pre-Celtic descent were turned officially into Goidels… It was necessary to discountenance the popular view that the Goidels were, comparatively speaking, late-comers to this country, and so the authors boldly and deliberately pushed back the Goidelic invasion into the remote past.”

This re-writing of history was eventually to have its desired result, as O’Rahilly noted with particular reference to the Cruthin: “The Cruthin or Priteni are the earliest inhabitants of these islands to whom a name can be assigned… The combined influence of Bede, Mael Mura, and the genealogical fiction of Ir, caused Cruithni to lose favour as the name of a section of the Irish population. This disuse of Cruithni as a name is doubtless connected with the rise of a new genealogical doctrine which turned the Irish Cruthin into Goidels and thus disassociated them from the Cruthin of Scotland. Nevertheless the fact that there were Cruthin in Ireland as well as in Scotland was, as might be expected, long remembered; and so it is not surprising to find writers occasionally suggesting, in defiance of Mael Mura, that the Cruthin of both countries formed one people in remote times.”

The Scottish Connection

It is to the ‘Scottish connection’ that we shall now turn. We have already seen that the link between Ireland and “Scotland” goes back to when people first established themselves in Ireland, one substantial piece of evidence being the appearance in both north-east Ireland and south-west “Scotland” of an identical type of megalithic grave — which have been labelled the ‘Clyde-Carlingford cairns’ by archaeologists to highlight the definite link across the North Channel. While the ease of accessibility provided by the narrow waters of the North Channel would lead us to suppose that commerce and movement between the two areas was of a regular and extensive nature, it is only as we approach the ‘historical’ age that documentary evidence is provided for such intercourse.

Possibly because of the pressure of the “Uí Néill” territorial gains, and the contraction of Old Ulster, groups within the Northern population began to move across the North Channel, in particular the Dál Riata, who settled Argyll and the islands along the western seaboard. The Venerable Bede, writing in the 8th century (A History of the English Church and People), states that this land was obtained from the local Pictish people by a combination of force and treaty. There was probably not much change in population, rather in cultural dominance. The kings of the Dál Riata soon claimed sovereignty over territory on both sides of the North Channel, ancient British Epidia and Robogdia. When the legendary Fergus Mac Erc, also known as Mac Nisse Mór, forsook his Irish capital of Dunseverick around 500 and established his main residence in Argyll, we may assume that by this time the Scottish dynasties had ousted the mother-country in importance. Carrickfergus is named after Fergus and he is reputedly buried nearby. While his historicity has been challenged by Scottish nationalist academics, there is no doubt of his symbolic importance in later Medieval Times.

After their defeat alongside Congal Cláen at the great battle of Moira in 637, however, the Dalriadan kings were finally to lose their Ulster territories to the “Uí Néill”. Groups from Ireland had been raiding Roman Britain, according to Roman writers, as early as 343. To the Romans the Irish raiders were called ‘Scotti’, and Ireland became known as Scotia. However, while Ireland was eventually to lose that appellation, the new rulers crossing the North Channel were to bequeath the name to their new homeland. From the kings of Dalriada there is a direct link to the kings of what would become ‘Scotland’.

The settlement of these northern Irish in Argyll has tended to overshadow a later movement across the North Channel — that of a migration of Cruthin to Galloway. As Charles Thomas wrote: “An admirable guide to the early Irish settlement could be constructed from the distribution of certain place-name elements — particularly those relating to simple natural features. [Such names are found in] an intense localized concentration in the double peninsula of the Rhinns of Galloway, opposite Antrim. No special historical sources describe what now looks like another early Irish colony here — possibly of the sixth century. But isolated archaeological finds from Galloway, the spread of a type of early ecclesiastical site (the enclosed developed cemetery) which may be regarded as Irish-inspired, and several minor pointers in the same direction, are mounting to reliable evidence for a separate settlement in this south-western area.”

The church at Bangor would have had strong links with this area, as it had through Comgall and Molua (Moluag) with the Picts (Caledonian Pretani), A Bangor monk became Abbot of St Ninian’s old monastery of Candida Casa at the end of the sixth century. Churches in Galloway were often

dedicated to saints popular in Ulster. Chalmers dated the main Cruthinic movements to the Galloway region to the eighth century “followed by fresh swarms from the Irish hive in the ninth and tenth centuries.” In Lowland Scots they would become known as Creenies or Kreenies.

Such a settlement by Ulster Cruthin may help to explain the references in old texts (Reginald of Durham, Jocelyn of Furness and Richard of Hexham) to the ‘Picts of Galloway’. Such references had troubled some historians, for the Scottish “Picts” were not believed to have dwelt so far south of the Antonine Wall, erected by the Romans to keep them at bay. However, the place-name and archaeological evidence indicating the link with Ulster provides an answer to the problem. Furthermore, the old Welsh records speak of the people of this area as Gwyddel Ffichti or ‘Irish Picts’.

These settlers had already absorbed the Gaelic language while in Ulster, and they were to carry it with them to “Scotland”, which eventually became named after them, “Scots” meaning Irish people. This new language, over the succeeding centuries, was eventually to spread throughout “Scotland”. The ancient traditions of Ulster which the settlers brought with them remained strong among the ordinary people long after they had disappeared from many parts of Ireland. Evidence of pre-Celtic and Celtic customs also abound throughout the Scottish-Irish ‘cultural province’ and much Ulster Folk material could still be collected in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland well into the 20th century.

The Pretani

With the arrival of the Christian period and the intensive missionary activity that spread to “Scotland”, initiated by men of vision and energy such as Comgall and Columba, the cross-fertilisation between “Scotland” and Ulster was to reach new heights, particularly in respect to the flowering of literary creativeness. As Proinsias Mac Cana wrote: “Isolation tends towards stagnation, or at least a circumscribed vision, while conversely intercourse and cultural commerce encourage a greater intellectual curiosity and awareness, a greater readiness to adapt old ways and experiment with new ones.”

“For such intercourse the east-Ulster region was ideally situated. It was a normal landing-place for travellers from northern Britain, which during the sixth and seventh centuries probably presented a more dramatic clash and confluence of cultures than any other part of Britain or Ireland; and, in addition, the religious, social and political ties that linked north-eastern Ireland and north-western Britain — particularly in that period — were numerous and close. Archaeologists speak of an ‘Irish Sea culture-province’ with its western flank in Ireland and its eastern flank in Britain; one might with comparable justification speak of a North Channel culture-province within which obtained a free currency of ideas, literary, intellectual and artistic.”

“One recalls particularly those tales which relate in one way or another to the commerce that existed between east-Ulster and Scotland: for instance, the story of Suibne Geilt, whom the later evolution of his legend makes king of Dál Riata—by James Carney’s reasoning it must have passed from Scotland to Ireland before c.800; or the several thematically related tales which make up what one might call the ‘Tristan complex’ and which also link Irish and north British tradition.”

The ancient inhabitants of the British Isles had been known to the Greeks as the ‘Pretani’. Later ‘Pretani’ became ‘Cruthin’ and when medieval Irish writers referred to these people it is clear they considered them to inhabit both Ireland and Scotland. One writer stated that ‘thirty kings of the Cruthin ruled Ireland and Scotland from Ollam to Fiachna mac Baetáin,’ and that ‘seven kings of the Cruthin of Scotland ruled Ireland in Tara ’ (secht rig do Chruithnibh Alban rofhallnastair Erind i Temair) — thereby identifying, as T.F. O’Rahilly notes, “the Cruthin of Ireland with those of Scotland”.

Others refer to Scotland as the ‘land of the Cruthin’, while in a poem written in the eleventh or twelfth century the author tells us that the Cruthnig made up a section of the population of Scotland. The Annals of Tigernach, The Pictish Chronicle, St Berchan, the Albanic Duan, the Book of Deer and John of Fordun plainly show that the name Cruthin was applied to the inhabitants of both Scotland and Ireland. The term in Scottish Gaelic for a Pict is Cruithen or Cruithneach and for Pictland Cruithentúath. Furthermore, the Pictish Chronicle has the first King of the Picts as the eponymous “Cruidne filius Cinge, pater Pictorum habitantium in hac insula. C annis regnavit“. This is entirely cognate with the eponymous founder of Gaeldom, Goidel Glas. The seven sons of Cruidne son of Cinge, also give their names to the ancient divisions of Alba.

The word ‘Pretani’ is also the forerunner of the Welsh Prydyn, still present in our modern British passports, which means primarily ‘Pict’ and secondarily ‘Pictland’ in Great Britain north of the Antonine Wall and Briton to the south of it. Eventually the Pretanic people of Scotland were to be more generally labelled Picts, though the Pretani of Ireland were never given this appellation by those writing in Latin (more modern writers, however, have quite freely interchanged the terms ‘Irish Pict’ and ‘Cruthin’). The Picts of Scotland did not disappear from history: as Liam de Paor points

out: “The Picts undoubtedly contributed much to the make-up of the medieval kingdom of Scotland, forming probably the bulk of its population.”

Because the ancient Irish considered the older inhabitants of Scotland and the northern part of Ireland to be from the same ethnic stock, it would be fascinating to know just how close that kinship was. Certainly, many factors lend weight to the probability that it was very close. For a start, the geographical proximity of Scotland and Ulster would certainly facilitate the same people establishing themselves on both sides of the North Channel. Scholars also acknowledge that the older population groups of Europe, if they survived reasonably intact at all under the impact of the Indo-European invasions, would have done so mainly at the peripheral fringes of the Continent, such as Ireland and Scotand.

Further, archaeologists now believe that the inhabitants of the ‘Highland zone’ of the British Isles — which includes Ireland and Scotland — are primarily of pre-Celtic stock. There are even indications of language similarities — when St Columba went to Scotland to try and convert the King of the Picts, he took with him St Comgall, the Cruthin abbot of Bangor, and St Canice, “who, being Irish Picts, were the better able to confer with the Picts [of Scotland].”

So, even if the archaeological and historical evidence may not as yet allow us to establish the exact extent of the kinship between the pre-Celtic peoples of Scotland and Ulster, there is at the same time nothing that necessarily contradicts the assertion of the ancient writers themselves that “the Cruthin of both areas formed one people in remote times.”

As Liam de Paor commented: “The gene pool of the Irish… is probably very closely related to the gene pools of highland Britain… Within that fringe area, relationships, both cultural and genetic, almost certainly go back to a much more distant time than that uncertain period when Celtic languages and customs came to dominate both Great Britain and Ireland. Therefore, so far as the physical make-up of the Irish goes… they share these origins with their fellows in the neighbouring parts — the north and west — of the next-door island of Great Britain.”

Just as the ‘Cruthin’ of Scotland eventually became known as Picts, so in Ireland, as we have already seen, the name Cruthin also fell into disuse, to be replaced by the names of their dynastic households. Yet, in 784 the Annals of Ulster recorded the death of Coisenech ‘nepos Predeni’, King of the Iveagh Cruthin. The existence of this pre-Gaelic name, Predeni (Pretani), so late in Irish history is astonishing, and shows how tenacious the Cruthin were to the memories of their former greatness.

The Age of the Vikings

Now we enter the Age of the Vikings, who were to leave a greater genetic footprint on England and Scotland than on Ireland. Their influence has remained however in Scots and Ulster Scots (Norse speech forms), English (Norman French word forms) and particularly Danish placenames in the former Danelaw of north-eastern England. In 793, the Danes attacked the Anglian monastery of Lindisfarne on the east coast of Britain, while on the west the Norse sacked the monastery of Iona in 795. In 811 the Ulaid clashed with the Norse Vikings and defeated them. In 823 the Norse pillaged Bangor monastery, in a devastating assault during which it is said that 3,000 people died, manuscripts were destroyed and the monastery utterly wrecked. In 825 they raided Downpatrick and Movilla, but were eventually badly beaten by the Ulaid in Leth Cathail (Lecale). By 870, Dumbarton Rock in Great Britain was home to a tightly packed Brittonic settlement, which served as a fortress and as the capital of Alt Clut (Strathclyde). The Vikings laid siege to Dumbarton for four months, eventually defeating the inhabitants when they cut off their water supply. The Norse king Olaf returned to the Viking city of Dublin in 871, with two hundred ships full of slaves and looted treasures. Olaf came to an agreement with Constantine of Scotland, and Artgal of Alt Clut. Strathclyde’s independence may have come to an end with the death of Owen the Bald, when the dynasty of Kenneth mac Alpin began to rule the region.

These repeated attacks occasionally met with concerted resistance. In 912, despite having been recently engaged in battle against one another, the Ulaid King, Hugh, and Niall Glundubh of the Uí Néill, agreed to a peace treaty which was ratified at Tullyhogue in Tyrone. The result was that, when Niall waged war on the Norse, the Ulaid were in support, and both kings fell together at the battle of Dublin in 919.

Yet despite the threat posed by these Scandinavian incursions, the internecine warring among the Irish continued as before, and the newcomers were inevitably drawn in. In 933 Matudan mac Hugh of the Ulaid raided Monaghan with Norse allies but was routed by the Uí Néill (Matudan is commemorated in Ben Madigan, now Cave Hill, overlooking Belfast). In 942 the Norse raided Downpatrick, but were defeated after a pursuit by the Ulaid. The following year the Ulaid of Lecale exterminated the Norse of Strangford Lough. In 949 Matudan made the fatal mistake of plundering the Cruthin of Conailli Muirthemne in Louth. The affront was avenged by the Iveagh Cruthin when they slew Matudan a year later.

The early raiding of these Scandinavian invaders gave way to the establishment of permanent settlements, the development of trade and commerce, and the founding of such centres as Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Wicklow, Cork and Limerick.

Despite this important contribution to Irish society, the Viking period is still regarded in the popular imagination as one of depredation and pillage. As Estyn Evans commented: “However much historians differ, there has been a tacit understanding that the “Celtic” invasion was somehow ‘good’… We have no record of what the natives thought about it. The Viking invasion on the other hand was ‘bad’: it came late enough for its misdeeds to be documented.”

Yet, if we consider the burning and pillaging of churches attributed to the Vikings by early Irish propagandists, it has been asserted that at least half of these, from the 7th century to the 16th, were perpetrated by the Irish themselves, not only before the Vikings came, but long after the Scandinavians were absorbed into Irish society.

At the battle of Hastings in 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, a descendant of Norse settlers in France, defeated the Anglo-Saxons and commenced the Norman conquest of England. It would not

be long before these Normans (Nor(d)manns) set foot in Ireland, though, ironically, not by ‘invasion’, but by ‘invitation’.

Another irony, as Lewis Warren points out, is that, despite the dramatic effect these new arrivals were to have on Irish history, “The English suffered more from the Normans than the Irish ever did. In Domesday Book there is no trace of the great families which had ruled England before 1066; in Ireland the leading families whose names are familiar from long before the Normans arrived are still there four hundred years later.”

In 1169 the first ‘Anglo-Normans’ arrived on Irish soil, at the request of Dermot Mac Murchada, deposed King of Leinster, who sought their aid in a bid to regain his kingship. The first to arrive were Norman knights like Fitzstephen and then Fitzgerald, and eventually families such as these would become ‘more Irish than the Irish’. The main contingent arrived with Strongbow (Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke) on 23 August 1170 at Waterford. Although these new arrivals are generally termed ‘Anglo-Norman’, it should be remembered that the Norman conquest of England and Wales was a relatively recent one. There the Norman French had many Old British (Brêtons) among them whose heritage was similar to the Welsh among whom they settled, and was expressed romantically in the Arthurian Chronicles. In actuality, therefore, Strongbow’s force was a Cambro-Norman one, and far from ‘English’ in either culture, language or composition.

Henry II was concerned with the growing independence of his supposed followers in Ireland. He arrived in Ireland to set matters straight, making his barons swear loyalty and then parcelling out the country between them and the Irish chieftains. As Lewis Warren commented: “Henry II had no intention of conquering Ireland; he wanted to stop the Normans doing it. He made a treaty with the High King by which he was to have charge of the Normans and Rory [O’Connor, king of Connaught] was to mind the Irish… Significantly he never included Ireland among his lordships. He was king of England, duke of Normandy, count of Anjou and duke of Aquitaine. That is how he styled himself: Ireland was not a welcome acquisition; it was a nuisance.”

In 1177 one of the baronial adventurers, John de Courcy, marched north and captured Downpatrick. What the Gaelic chieftains had begun but not completed — the final end to Ulster’s independence — was now to be accomplished by de Courcy, who made himself ‘Master of Ulster’ (princeps Ultoniae). Although he owed fealty to Henry II of England, this title was purely of de Courcy’s own making. The Ulidian king, Mac Donleavy, still officially remained ‘Rex Ulidiae’.

De Courcy’s greatest achievements were the establishment of towns and ports and the building of two fine castles, at Carrickfergus and Dundrum. At first strongly opposed by the Ulstermen, de Courcy’s government was soon seen by them to offer some degree of protection against continuing attacks by the O’Neills. In 1181 the Clan Owen “gained a battle over the Ulidians, and over Uí Tuirtri, and over Fir-Li around Rory Mac Donleavy and Cumee O’Flynn.”

A descendant of Rory, J P Donleavy, wrote The Ginger Man, considered by The Modern Library as one of the 100 best novels. First published in Paris in 1955, it was once banned in the Republic of Ireland and The United States of America. Perhaps we will still see a film adaptation starring Johnny Depp. The material you are now reading was also once destined for burning by the Irish Academic Establishment.

Increasing raids by the Clan Owen in which they “took many thousands of cows” forced the Ulidians to appeal to de Courcy for help. And so, when the O Neills and their kin made their next raid in 1182, they were met and defeated by de Courcy in alliance with the Ulidians.

De Courcy’s independent rule in Ulster now aroused the jealousy of Hugh de Lacy, who misrepresented the Master of Ulster to the new King John of England. Following this de Courcy fell into disfavour, and was defeated by de Lacy at Downpatrick. Finally, on 29 May, 1205, King John granted de Lacy all of de Courcy’s lands, and created him Earl of Ulster. De Lacy and his half-brother Walter soon showed John that he had mistaken his men, for by 1208 they were at war with ‘the English of Munster’, and proved more insubordinate than the Irish themselves.

The Earldom of Ulster – The Bruce Brothers

Although the Gaelic chiefs continued to resist the Anglo-Norman presence, this did not inhibit constant warfare between the O’Donnells of Tirconnell and the O’Neills of Tirowen. In 1258 a conference was held to promote a spirit of unity among the Gaelic chiefs. At this gathering Brian O’Neill was elected ‘high-king’, although important figures such as Donald Oge O’Donnell refused to acknowledge him. One result, however, was the forging of an alliance between Brian O’Neill and Felim O’Connor, King of Connacht. This alliance was crushed by the ‘English’ at the battle of Downpatrick in 1260. The Iveagh Cruthin and the Ulaid refused to join the O’Neills at this battle, a confirmation perhaps that in Ireland deep-seated antagonism to old enemies can last a very long time.

As the Anglo-Norman expansion continued, the O’Neills still coveted each other’s property. In 1275 the Tirowen (Tyrone) families invaded Tirconnell and devastated the entire district. Following this incursion they were pursued by O’Donnell of Tirconnell and defeated “with the loss of men, horses, accoutrements, arms and armour.” In 1283 the positions were reversed, and it was the turn of Tirconnell to be heavily defeated by O’Neill of Tirowen. The ‘English’ of the north were now led by Richard de Burgh, the ‘Red Earl of Ulster’.

Richard’s father Walter had inherited the de Lacy territory by right of his wife, who was Hugh de Lacy’s daughter. So, in 1286, we find Richard compelling the submission of the O’Donnell. He also deposed the O’Neill of Tyrone for a time, and in 1290 again plundered Tirconnell. Later he planted a colony in Inishowen and erected a castle at Moville to command the whole district. A descendant through his mother is the singer/songwriter Chris de Burgh and directly my old friend Coralie de Burgh Kinahan and her son Danny.

On 24 June 1314 the Scots, under Robert the Bruce, defeated the English at the battle of Bannockburn. The natural extension of the victory of Scottish independence was the invitation of O’Neill of Tyrone to Robert offering to make his brother Edward — then ‘Lord of Galloway’ — King of Ireland. Robert accepted readily for the fierce ambition of his brother was a threat to the King of Scots himself.

And so, on 25 May, 1315, Edward Bruce landed at Larne Harbour on the Antrim coast. He was joined by Robert Bissett with the Scots of Antrim and by Donald O’Neill son of Brian of Tyrone.In response to this threat, and in spite of his age, Richard, the Red Earl of Ulster, assembled his retainers in Roscommon and marched to Athlone, where he was joined by Felim O’Connor and the army of Connacht. This ‘English’ army then marched into Ulster, laying waste the country of the O’Neill.