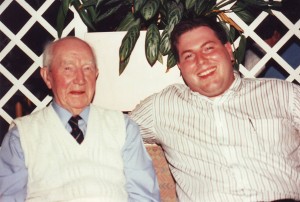

James Taylor(A.S.C.) with my nephew Kevin Ian Beegle at Albert, France- 1996

I think that this was taken at the restaurant in Albert. If I remember correctly the owners Grandfather was a veteran and he brought out a special bottle for James to try. James handled it better than me. He was such a character! ..Kevin Ian Beegle

The Somme Association Interviews James Taylor

James was born in Belfast on 12th February 1899. He attended Dewar’s School on Donegall Pass, Belfast. My first question to James was, had he enjoyed his days at school? “Yes, I did, but I often ‘mitched’ (played truant). My mother would take me to school and I’d go up the stairs to the school above, but as soon as she’d gone I would go down the back stairs and away. But I enjoyed my time at school.”

James left school aged eleven and began working almost immediately. He recalls his very first job. “I began working in a grocer’s shop called Fitzpatrick’s: it was in Rugby Avenue. I stayed there for about two years I think, and it was long hours. I started at 9 o’ clock in the morning and finished at 6 o’ clock at night. I was paid two shillings and sixpence per week.”

James’s next job was at Fowler’s Mineral Water Company. He was working here at the outbreak of the First World War. “I left and joined the navy in 1914 but I was sent home because of my age and also I was the only male in the family. My father died when I was three years old.”

James stayed at home until late in 1916 when he once again joined the ‘Colours’. This time it was not the navy but the Royal Field Artillery. Was there any particular reason he chose the Artillery? “I could ride a horse, but I still had to go through the riding school just the same.”

James trained at Athlone, and then at Edinburgh. The day James enlisted he met another young man, Billy Ferguson, also from Belfast, who was also joining the R.F.A. and they became good friends. James was very upset when at the dispersal unit they were posted to different units. He recalls that time with sadness. “We pleaded with them to let us stay together but it was no use. They wanted only one man for each battery so we were split up. That was the last time I saw him. He was killed on 4th July 1918 near Amiens.”

James went to France early in 1917 and his first taste of action was at Vimy Ridge, when the Canadians did what most thought was impossible – they captured the Ridge. What was his clearest memory of Vimy? “I happened to be down in the tunnels when a German plane dropped a bomb. Well, it was a million to one chance but it bounced down the stairs at the entrance and exploded. It killed quite a few men.”

I wondered what conditions had been like down those tunnels. James supplied the answer. “It was cold and damp. You had a couple of boards to sleep on and of course we had lice, rats and mice. I remember once, my mother sent me out a food parcel; she must have thought I was being starved. Well, I just put it under my pillow that night, but the next morning there was nothing left. The rats had got it.”

James belonged to what he refers to as a ‘Flying Column’, attached to 277 Army Brigade, and his battery relieved other batteries who were coming out of the Line for a rest. Did he see anything of the 16th (Irish) or 36th (Ulster) Divisions? “Oh yes, we relieved them all. Anytime there was going to be a big bombardment we were sent as extra guns to help out.”

The R.F.A., like most regiments of the British Army, suffered tremendous casualties and, of course, besides men, they lost thousands of horses and mules. James remembers one night that, thankfully, no men were killed, but they lost many horses. “We had just tied up the horses when ‘Jerry’ started shelling and we dived down into the cellar of a house. After the shelling stopped, we came out to discover the roof of the house had been blown off by a shell and all the horses had been killed.”

I asked James if his battery had ever fired gas shells. “I don’t remember ever firing them, but we may have. I remember once we were attacked with gas shells – of course the first thing you had to do was make sure that you got the horses’ masks on first.”

I asked James what would have happened had the men put their masks on first? His reply amazed me. “I think we would have been shot. It (gas) was a terrible thing to use on men. Once I saw about thirty men with hands on one another’s shoulders. They had been blinded by gas.”

James’s battery continued to see action, relieving other batteries of the R.F.A. What, I wondered, was the greatest danger while firing the guns? James gave two examples.” The greatest danger was, of course, the enemy artillery. The other was the planes.”

How did the artillery cope with the planes? “We kept our rifles on the gun carriage, and at one end of the battery we had a machine-gun so if a plane came too close we could chase it away.”

Both the British and German planes often engaged in ‘dog-fights.’ Had James ever witnessed one of these engagements? “Yes, I did. I saw one and there were quite a few planes taking part. I saw some of the planes go up in smoke and crash to the ground, but one thing we watched nearly every day was the observation balloons being attacked and the men dropping out by parachute.”

James served until the Armistice and was fortunate enough to suffer only a slight shrapnel wound during his service. After the Armistice James was demobbed, but he was not too happy. He explained: “One day, just at the beginning of January 1919, I think it was, our Major, Major Bibby, whose family owned the Bibby Shipping Line, called me into his office and told me I was going home. I said, ‘But I don’t want to go home, I want to stay with the unit.’ He told me he had no say in the matter as I was a volunteer, the only volunteer in the battery, so you are first home. Tomorrow morning you will collect your rations and rail warrant and away you go. I was very disappointed but there was nothing I could about it.”

So now James was on his way home: did he go straight to Ireland? “No, I went to Wales, to a dispersal unit where I handed in my uniform, had a shower and was then given a new uniform and a kit bag. I was allowed to keep my helmet. I stayed there a couple of days and was then sent to Dublin.”

I then asked James if his helmet was the only souvenir he brought back? James laughed as he explained. “No, I had an automatic pistol that I got off a German; that was the first thing they took off me. It went into a big bin which was full of pistols and rifles. No-one from Ireland was allowed to keep a gun as a souvenir.”

James then went straight to Belfast. Did he go into barracks? “No, straight home. My mother was delighted to see me. She didn’t know I was coming home: I hadn’t time to send word.”

James quickly settled back into civilian life and got a job in the County Down Railway, but it didn’t last long. His next job was as a docker in Belfast, a job which he was to hold until his retirement at age 65. Did James enjoy his years as a docker? “Very much and it was well paid. We worked in what was known as a ‘gang’, with maybe up to 19 men in a gang. We sometimes earned 33 shillings a day, twice as a much as a shipyard worker earned and I enjoyed the work. I was sorry I had to retire.”

I asked James to sum up his time in the army. I think his answer is typical of those men who served in the First World War. “There were some bad times and I suppose some good times. The best thing was the friends you made: we looked after each other. But sitting at night with a ground sheet and the rain pouring down on you wasn’t very pleasant.

James Taylor to my mind is typical of the men who served during ‘the war to end all wars.’ Never once during our conversation did he complain about his time in the army, or the terrible conditions they had to endure. I leave the last word to James. “We had a duty to perform and we did it to the best of our ability. But when I saw the way the men were treated when they came home, I wonder was it all worth it.”

Mr Taylor and Mr Currie lay their wreaths

In 1996 James, together with fellow veteran 98 year old Mr Harry Currie (A.S.C.), was the guest of the Somme Association at the 80th Anniversary Ceremony of the Battle of the Somme in France. During the visit, James visited the grave of his friend Billy Ferguson at Crucifix Corner Cemetery at Villiers Bretonneux to pay his last respects. It was a most moving moment.

James Taylor sadly passed away in 2000.