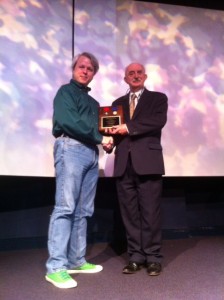

Today I accompanied my colleague in Pretani Associates, Helen Brooker, to the St Patrick’s Centre, Downpatrick, County Down on the invitation of its Director Tim Campbell, and gave a lecture on Common Identity to the American National Society Sons of the American Revolution. They presented me with The International Medal and the Commodore John Barry Medal in honor of Irish Patriots of the American Revolution 1775-1783. I was highly honoured to meet this great society.

To the Irish the main credit for the introduction of Christianity to Ireland belongs to St Patrick, so that every 17th March we celebrate St Patrick’s Day. Yet, despite Patrick’s pre-eminent place in the history of the Irish Church, we do not know just how much of his story is historically accurate. Ironically, the only first-hand accounts of Patrick come from two works which he reputedly wrote himself, the Confession and the Epistle to Coroticus.

To the Irish the main credit for the introduction of Christianity to Ireland belongs to St Patrick, so that every 17th March we celebrate St Patrick’s Day. Yet, despite Patrick’s pre-eminent place in the history of the Irish Church, we do not know just how much of his story is historically accurate. Ironically, the only first-hand accounts of Patrick come from two works which he reputedly wrote himself, the Confession and the Epistle to Coroticus.

Further, the reference to his arrival in the Annals cannot be taken as necessarily factual either, as it is now believed that the Annals only became contemporary in the latter part of the sixth century, and fifth century entries were therefore ‘backdated’. The question of Palladius and his mission from Rome leads to still more uncertainty, with some scholars even proposing the idea that there could have been ‘two’ Patricks. Francis Byrne suggested that “we may suspect that some of the seventh-century traditions originally referred to Palladius and have been transferred, whether deliberately or as a result of genuine confusion, to the figure of Patrick.”

This uncertainty must be borne in mind when we come to look at his story. He was born towards the end of the fourth century in Bannaven Taberniae, a village somewhere in Romanised Britain. His father was Calpornius, a deacon, who was the son of Potitus. Patrick was brought up in a small villa not far away, where, he says, he was made captive at the age of about 16 years and taken to Ulster as a slave and and sold to a Cruthinic chieftain called Milchu, (Miliucc moccu Boin)-of the Bonrige or Dal mBoin, who used him to tend flocks around Mount Slemish near Ballymena in County Antrim. After six years of servitude he managed to escape from Ireland, first going by boat to the Continent, then two years later returning to his parents in Britain. It is thought that during this period he learned the divine wisdom of Marmoutiers.

Despite his parents being anxious that he would now remain at home, Patrick had a vision of an angel who had come from Ireland with letters. In one of these was relayed the message: “We beg you, Holy youth, to come and walk amongst us once again.” To Patrick, the letters “completely broke my heart and I could read no more and woke up.” Tradition tells that Patrick eventually made the journey back to Ireland, finally landing in Lecale, County Down in the territory of Dichu (of the Ulaid) who became his first convert. Dichu’s barn (sabhall or Saul) near Downpatrick was the first of his churches. So deep was the faith of Patrick that it is said that, “each night he sang a hundred psalms to adore the King of Angels”.

Not everyone was necessarily overjoyed to see the return of Patrick. His old master Milchu, a convinced pagan, when forewarned of an impending visit by Patrick, set fire to his house and all his property, then perished in the flames rather than risk being converted. Nor was every conversion lasting — King Laeghaire, despite being baptised, remained pagan at heart and was buried at his own request with pagan rites. Estyn Evans wrote that “Professor R.A.S. Macalister of University College, Dublin, a Gaelic enthusiast turned cynic, used to say in private that the number of believing Christians in the early centuries of Christianity could probably be reckoned by counting the number of Irish saints.”

Among those who accompanied St Patrick was St Sechnall who was the earliest Christian poet in Ireland. It was in St Sechnall’s church of Dunshaughlin that the beautiful eucharistic hymn Sancti Venite was first sung. The tradition was that this incomparable hymn was chanted by a choir of angels during the Holy Communion and hence arose the custom ever afterwards in Ireland of singing this hymn at the Communion. Hence, too, the title which the hymn bears in the Bangor Antiphonary, which is the only ancient work in which it is found, “Hymn during the Communion of the Priests”.

Two stanzas are as follows:

“Sancti Venite “Draw nigh, ye Holy ones,

Christi Corpus Sumite And take the body of the Lord.

Sanctum bibentes And drink the sacred blood He shed

Quo redempti sanguinum For your redemption

Alpha et Omega, The beginning and the end,

Ipse Christus Dominum The Christ, The Lord,

Venit venturus Who comes and will come again

Judicare homines” To judge all men”

To be continued

© Pretani Associates 2014