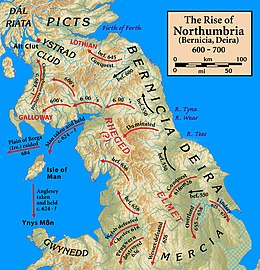

Northumbria was originally composed of the union of the two independent Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Bernicia, the former British kingdom of Bryneich and Deira, the former British kingdom of Deifr or Dewr. Bernicia covered lands north of the Tees, while Deira corresponded roughly to modern-day Yorkshire, absorbing the British Kingdom of Elmet. Bernicia and Deira were first united by Aethelfrith, a king of Bernicia, who conquered Deira around the year 604. He was defeated and killed around the year 616 in battle at the River Idle by Raedwald of East Anglia, who installed Edwin, the son of Aella, a former king of Deira, as king.

Edwin, who accepted Christianity in 627, soon grew to become the most powerful king in England. He was recognised as Bretwealda or Ruler of all Britain and its islands, including Ireland, the original Islands of the Pretani, and he conquered the Isle of Man amd Gwynedd in Northern Wales. He was, however, himself defeated by an alliance of the exiled king of Gwynedd, Cadwallon ap Cadfan and Penda, king of Mercia, at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633.

After Edwin’s death, Northumbria was split between Bernicia, where Eadfrith, a son of Aethelfrith, took power, and Deira, where a cousin of Edwin, Osric, became king. British Cumbria tended to remain a country frontier with the Britons. Both of these rulers were killed during the year that followed, as Cadwallon continued his devastating invasion of Northumbria. After the murder of Eanfrith, his brother, Oswald, backed by warriors sent by Domnall Brecc of Dalriada (Dál Riata), defeated and killed Cadwallon at the Battle of Heavenfield in 634.

Oswald expanded his kingdom considerably. He incorporated Gododdin lands northwards up to the Firth of Forth and also gradually extended his reach westward, encroaching on the remaining British speaking kingdoms of Rheged and Strathclyde. Thus, Northumbria became not only part of the far north of modern “England”, but also covered much of what is now the south-east of modern “Scotland”. King Oswald re-introduced Christianity to the Kingdom by appointing St Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona to convert his people. This led to the introduction of the practices of “Celtic” Christianity and a monastery was established on Lindesfarne.

War with Mercia continued, however. In 642, Oswald was killed by the Mercians under Penda at the Battle of Maserfield. In 655, Penda launched a massive invasion of Northumbria, aided by the sub-king of Deira, Aethelwald, but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of an inferior force under Oswiu , Oswald’s successor, at the Battle of Winwaed. This battle marked a major turning point in Northumbrian fortunes: Penda died in the battle, and Oswiu gained supremacy over Mercia, making himself the most powerful king in England.

In the year 664 the Synod of Witby was held to discuss the controversy regarding the timing of the Easter festival. Much dispute had arisen between the practices of the “Celtic” church in Northumbria and the beliefs of the Roman church. Eventually, Northumbria was persuaded to move to the Roman practice and the Celtic Bishop Colman of Lindesfarne returned to Iona.

Northumbria lost control of Mercia in the late 650s, after a successful revolt under Penda’s son Wulfhere, but it retained its dominant position until it suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Picts at the Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685; Northumbria’s king, Ecgfrith (son of Oswiu), was killed, and its power in the north was gravely weakened. The peaceful reign of Aldfrith, Ecgfrith’s half-brother and successor, did something to limit the damage done, but it is from this point that Northumbria’s power began to decline, and chronic instability followed Aldfrith’s death in 704.

In 867 Northumbria became the northern kingdom of the Danelaw, after its conquest by the brothers Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless who installed an Englishman, Ecgberht, as a puppet king. Despite the pillaging of the kingdom, Viking Rule brought lucrative trade to Northumbria, especially at their capital York. The kingdom passed between English, Norse and Norse-Gaelic kings until it was finally absorbed by King Eadred after the death of the last independent Northumbrian monarch, Erik Bloodaxe, in 954.

After the English regained the territory of the former kingdom, Scots invasions reduced Northumbria to an earldom stretching from the Humber to the Tweed. Northumbria was disputed between the emerging kingdoms of England and Scotland. The land north of the Tweed was finally ceded to Scotland in 1018 as a result of the Battle of Carham. Yorkshire and Northumberland were first mentioned as separate in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1065. William the Bastard became king of England in 1066. He realised he needed to control Northumbria, which had remained virtually independent of the Kings of England, to protect his kingdom from Scottish invasion. In 1067, William appointed Copsi (sometimes Copsig) as Earl. However, just five weeks into his reign as earl, Copsi was murdered by Osulf II of Bamburgh.

To acknowledge the remote independence of Northumbria and ensure England was properly defended from the Scots, William gained the allegiance of both the Bishop of Durham and the Earl and confirmed their powers and privileges. However, anti-Norman rebellions followed. William therefore attempted to install Robert Comine, a Norman Noble noble, as the Earl of Northumbria, but before Comine could take up office, he and his 700 men were massacred in the city of Durham. In revenge, the now “Conqueror” led his army in a bloody raid into Northumbria, an event of ethnic cleansing that became known as the harrying of the North. Ethelwin, the Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Durham, tried to flee Northumbria at the time of the raid, with Northumbrian treasures. The bishop was subsequently caught, imprisoned, and later died in confinement; his seat was left vacant.

Rebellions continued, and William’s son William Rufus decided to partition Northumbria. William of St Carilef was made Bishop of Durham, and was also given the powers of Earl for the region south of the rivers Tyne and Derwent, which became the County Palatine of Durham.The remainder, to the north of the rivers, became Nothhumberland, where the political powers of the Bishops of Durham were limited to only certain districts, and the earls continued to rule as clients of the English throne. The city of Newcasltle was founded by the Normans in 1080 to control the region by holding the strategically important crossing point of the river Tyne.

The flag of the kingdom was “a banner made of gold and purple” (or red), first recorded in the 8th century as having hung over the shrine of King Oswald. This was later interpreted as vertical stripes. A modified version (with broken vertical stripes) can be seen in the coat of arms and flag used by Northumberland County Council.

Northumbria during its “golden age” was the most important centre of religious learning and arts in the British Isles. Initially the kingdom was evangelised by Irish monks from the “Celtic” Church, based at Iona in modern Scotland, which led to a flowering of monastic life. Lindesfarne on the east coast was founded from Iona by Saint Aidan in about 635, and was to remain the major Northumbrian monastic centre, producing figures like Wilfrid and Saint Cuthbert. The nobleman Benedict Biscop had visited Rome and headed the monastery at Canterbury in Kent and his twin-foundation Monkwearmouth -Jarrow Abbey added a direct Roman influence to Northumbrian culture, and produced figures such as Coelfrith and Bede.

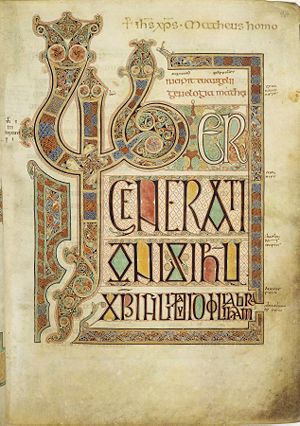

Northumbria played an important role in the formation of Insular Art, a unique style combining Anglo-Saxon, Pictish, Byzantine and other elements, producing works such as the Lindesfarne Gospels. St Cuthbert Gosplel, the Ruthwell Cross and Bewcastle Cross, and later the Book of Kells, which was probably created at Iona. After the Synod of Whitby in 664 Roman church practices officially replaced the “Celtic” ones but the influence of the “Celtic style continued, the most famous examples of this being the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Venerable Bede (673–735) wrote his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed in 731) in Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, and much of it focuses on the kingdom. The devastating Viking raid on Lindisfarne in 793 marked the beginning of a century of Viking invasions that severely checked all Anglo-Saxon culture, and heralded the end of Northumbria’s position as a centre of influence, although in the years immediately following confident works like the Easby Cross were still being produced.

Northumbria has its own check or tartan, which is similar to many ancient tartans (especially those from Northern Europe, such as one found near Falkirk and those discovered in Jutland that date from Roman times (and even earlier). Modern Border Tartans are almost invariably a bold black and white check, but historically the light squares were the yellowish colour of untreated wool, with the dark squares any of a range of dark greys, blues, greens or browns; hence the alternative name of “Border Drab”. At a distance the checks blend together making the fabric ideal camouflage for stalking game.

The most persistent influence of Northumbria, however, is its language. From Old Northumbrian English developed modern Geordie and other variants, i.e. Northern (north of the Rver Coquet), Western (from Allendale through Hexham up to Kielde), Southern or Pitmatic (the mining towns such as Ashington and much of Durham), Mackem (Wearside), Smoggie (Teeside) and possibly also Tyke (Yorkshire). It is spoken mainly if not exclusively in the modern day counties of Northumberland and Durham. Whilst all sharing similarities to the more famous Geordie dialect and most of the time not distinguishable by non-native speakers, there are a few differences between said variants not only between them and Geordie but also each other. Yet the most prominent derivative of Old Northumbian English is modern Scots and its variant Ulster-Scots, also known as Scotch-Irish or Ullans. The latter term I created as a neologism to differentiate the language from Ulster-Scots or Scotch Irish traditions and it has found its way into the Belfast Agreement through my fiends David Trimble and David Campbell of the Ulster Unionist Party.

To be continued

© Pretani Associates 2014