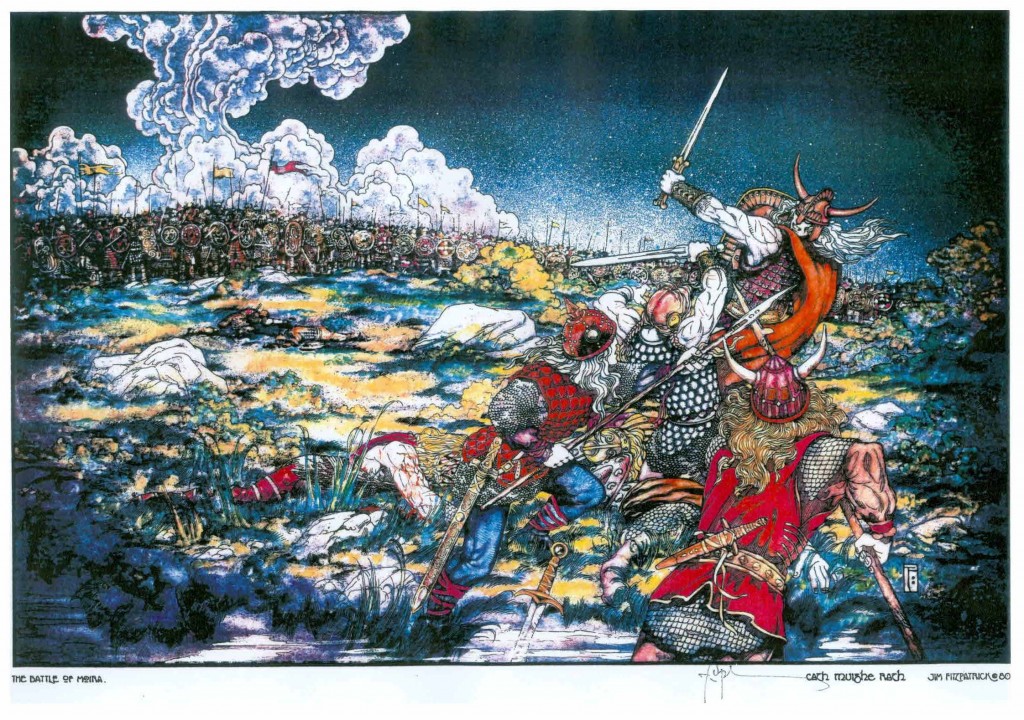

On 24th June, 637 AD therefore was fought the famous Battle of Magh Rath (Moira) in County Down against Domnall, son of Hugh, by the allies of Ulster. Sadly, however, Congal was killed and Domnall Brecc (Freckled Donald), King of Dalriada, lost all his Ulster territories. In this way the Ui Neill consolidated their power in Ulster and the Cruthin further declined. One of the finest passages from the epic of the Belfast poet and antiquarian, Sir Samuel Ferguson, on Congal is the soliloquy of Ardan, the great friend of Congal, to his dead king following the battle.

On 24th June, 637 AD therefore was fought the famous Battle of Magh Rath (Moira) in County Down against Domnall, son of Hugh, by the allies of Ulster. Sadly, however, Congal was killed and Domnall Brecc (Freckled Donald), King of Dalriada, lost all his Ulster territories. In this way the Ui Neill consolidated their power in Ulster and the Cruthin further declined. One of the finest passages from the epic of the Belfast poet and antiquarian, Sir Samuel Ferguson, on Congal is the soliloquy of Ardan, the great friend of Congal, to his dead king following the battle.Last wreck remaining of a power and order overthrown,

Much needing solace;

And, ah me!, not in the empty lore

Of bard or druid does my soul find peace or comfort more;

Nor in the bells or crooked staves nor sacrificial shows

Find I help my soul desires,

Or in the chants of those

Who claim our druids’ vacant place.

Alone and faint, I crave,

Oh, God, one ray of heavenly light to help me to the grave,

Such even as thou, dead Congal, hadst;

That so these eyes of mine

May look their last on earth and heaven with calmness such as thine.”

The story of the Donegal Kingdoms , describing them as “Northern Ui Neill”, rather than the Venniconian Cruthin that they actually were , is a later propagandistic fiction and not a summary of what actually happened. Almost certainly it was given its classical form by and on behalf of the Cenel nEogan, during the reign in the mid eighth century of their powerful and ambitious king, Aed (Hugh) Allan, who died in the year 743. Whatever his actual victories and political successes, they were underlined by a set of deliberately created fictional historical texts which purported to give him and his ancestors a more glorious past than they had actually enjoyed. The same texts projected his dynasty back to the dawn of history and created a new political relationship with the neighbouring kingdoms. Whatever the initial reaction to them, these political fictions were plausible enough to endure and have been ultimately accepted as history by most commentators over the past thirteen hundred years and by those modern “serious scholars” trapped in nationalist ideologies.

Aed’s pseudo-historians were probably led by the Armagh Bishop Congus, who exploited the opportunity provided by the alliance with the King to advance the case for the supremacy of his own church throughout Ireland. Congus was from Cul Athguirt in the parish of Islandmagee, County Antrim. He was descended from Dá Slúaig, the son of Ainmere so he was a member of the Húi Nadsluaga clan who were one of the five prímthúatha of the Dál mBuinne Cruthin, east of Lough Neagh, County Antrim. Congus was a scribe before being elevated to the See of Armagh. He died in 750.

The Bangor Antiphonary itself may be dated from Cronan, the last Abbot listed in the commemoration poem, who, according to the Annals, died on 6 November, 691 AD. Cronan was alive when the Antiphonary was written so that it follows that it can be dated some year between 680 and 691. The manuscript was given its present title “Antiphonarium Benchorense” by the great Italian scholar, Muratori. It remains the only important relic of the ancient monastery of Bangor and was taken from Bangor to Bobbio at some time between its composition and the plundering of the monastery by the Vikings in the ninth century.

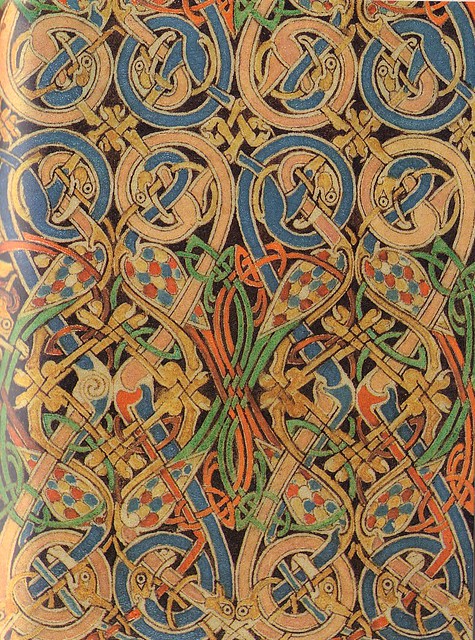

Indirect evidence of the work of the Bangor monks, however, is found in early Christian ornamentation. Pictish artwork is strongly characterised by intricate network interlacing. This is apparent in ornamental stones found on the east coast of Scotland and England from Shetland to Durham and in parts of Ireland. Identical features are also found in the great contemporary illuminated gospels of Durrow, Lindesfarne and Kells. The Book of Durrow is named after the Columban foundation of Durrow near Tullamore in Offaly. It is generally regarded as having been made towards the end of the seventh century, perhaps in the 670s, and Cruthinic influence was outstanding.

But the finest surviving example of the Pictish art form lies in the Lindesfarne Gospels which were written in honour of St. Cuthbert by Eadfrith who was made Bishop of Lindesfarne in the year of our Lord 698. These were bound by Bishop Ethilward and ornamented by Bilfrith the anchorite. The great work was preserved with the body of the saint at Lindesfarne and then carried in flight before the fury of the Vikings. Having rested some years at Durham, it was finally returned to Lindesfarne Priory where it stayed until the Dissolution.

The Book of Kells is generally assigned to the early ninth century when it may have been written and illuminated by the scribes of Iona. Subsequently it was brought to Kells where it was known in the eleventh century as “The great gospel of Colum Cille (Columba).” There are many influences apparent in its design, notably the Coptic (Egyptian), Cruthinic (Pictish) and Celtic, all three of which were prominent in Bangor until its destruction. For example, Christ is symbolised by the Greek letters “Xp” (Chi Rho) in both the Book of Kells and the Bangor Antiphonary.

Yet because of its location on the shores of Belfast Lough the great monastery lay open to attack by the Vikings. They first came raiding in the year 810 AD and between 822 and 824 the tomb of Comgall was broken open, its costly ornaments seized and the bones of the great saint “shaken from their shrine.” St. Bernard related that on one day alone 900 monks were killed. It is unlikely that following this time the Laus Perennis was ever sung again in Ireland.

To be continued

© Pretani Associates 2014