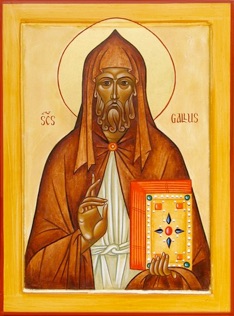

Too frail to accompany his abbot, Gallus, or as we know him now, St Gall, left Columbanus’s mission in 612 AD to stay in Swabia and live in a retreat by the Steinach. At this site in 720, an Abbey was eventually formed by the Alemannian Ottmar which bears Gall’s name, St Gallen. In 747 Abbot Ottmar was required to convert the community to Benedictine ways. He thus designated buildings for common dining and sleeping with an infirmary and hospice. But the Abbey’s lands were totally alienated by greedy neighbours and it ceased to prosper.In 816 however Gozbert arrived as Abbot to find the monk’s spiritual life at a low ebb. Through vigorous litigation he reclaimed the estates of the Abbey and regained its fortunes. By 830 AD he was ready to refurbish the superannuated buildings of the old settlement and for this purpose he requested the guidance of The Plan of St Gall, the document created as an instrument of policy to inform and regulate monastic planning throughout the Frankish Empire.

In August 1988, while Chairman of the Farset organisation, I initiated a meeting with Cardinal Tomas O Fiaich at the Bangor Heritage Centre, when a video recording of the Cardinal speaking about Columbanus took place. He was then received by the Mayor of North Down. We then met Archbishop Robin Eames, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of the Church of Ireland, on Friday 2 September 1988 to tell him of our proposal to make a video, which was to be entitled The Steps of Columbanus. He too agreed to support it by participating in the video, giving a talk on Comgall. This was subsequently done under the auspices of Canon Hamilton Leckey at Bangor Abbey.

On Monday, 5 September 1988 I took Jackie Hewitt from the Farset Youth Project to follow part of the route Columbanus had taken. We stayed the following night at the home of Raymond Laurent, one of my closest Parisian friends. We travelled on to Auxerre, where both Columbanus and Patrick studied, and arrived in Lausanne where we had dinner with Pierre Dubois, Professor of European Studies at the University of Geneva. We then crossed the Alps via the St Gothard Pass, on the same route as Columbanus, going on to Milan and eventually to Bobbio where the saint rests.The full route, however, would be covered by the audio-visual unit itself the following year.

In September 1989, therefore, the audio-visual project took place with Bahman Jamshid Nehad, an Iranian Project Superviser, as our co-ordinator and Henry Mohammed as our camera-man. We visited Rheims, Luxeuil, the Rhine, St Gallen, Bregenz and Bobbio. Barney McCaughey acted as narrator and the initial video presentation was presented to Cardinal Tomàs Ó Fiaich and Archbishop Eames along with the Arts Council of Northern Ireland and the Cultural Traditions Group of the Community Relations Council, of which I was a member, early in 1990. It was hoped that the BBC and RTE would attend, but, of course, they didn’t. For they never do.

It was indeed most interesting to visit the library of the great church of St Gallen in Switzerland, the destination to which the ‘Plan of St Gall’ was originally sent some 1200 years ago at the abbot’s request. The simple survival of the plan is something of a wonder. And although it describes a self-contained monastic community, it reveals an astonishing congruence with modern concerns of community planning, technology and the efficient use of resources. Indeed essential unity of purpose expressed therein sustains its timeless relevance to human needs and western society.

The Carolingian empire, left to the lesser scions of a great house, broke up after the death of its founder. But the ideals of Charlemagne, and indeed Columbanus before him, survive in a document which became an important force in the shaping of modern Europe. For like the concept of empire itself the scheme transmitted to us in the Plan of St Gall, was to survive the collapse of that power which first nurtured it and left a permanent imprint on monastic planning for centuries to come.

To be continued

© Pretani Associates 2014